On March 20, 1861, Charles P. Mattocks, a college student at Bowdoin College in Maine, entered the office of his German and elocution professor, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, to discuss Mattocks’ slipping academic rank. After their conversation, a rejuvenated Mattocks wrote in his diary, “I am determined, and there’s no such word as fail now.”

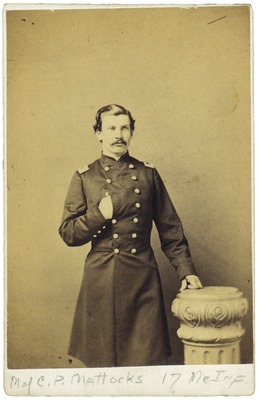

As Charles Mattocks concentrated on his studies, the nation broke apart. In May, Mattocks helped form a military company among the students. Although still enrolled, they practiced drills in their spare time and learned the rudiments of military life. Upon graduation in 1862, Mattocks joined the 17th Maine Infantry as a first lieutenant.

After serving with his regiment during the Battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, and enduring the hardships of camp life, Mattocks’ reputation as a no-nonsense officer led to him being placed in command of the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters in March 1864. Less than two months later, at the Battle of the Wilderness, Mattocks was captured and sent to an officers’ prison in Macon, Georgia. Moved to South Carolina, Mattocks and two other officers escaped but were recaptured after more than three weeks on the run. Mattocks was eventually exchanged and rejoined his original regiment, the 17th Maine, on March 31, 1865.

By the time Mattocks rejoined the Army, General Ulysses S. Grant was determined to break the nine-month stalemate near Petersburg, Virginia. He struck Confederate positions at Five Forks on April 1, threatening General Robert E. Lee’s access to the South Side Railroad, his last supply line. The next day Grant launched an offensive along the trenches that defined the battle lines of both armies. Unable to stop the Union onslaught, Lee knew he had to abandon both Petersburg and Richmond to the north. Lee moved his forces west attempting to reach General Joseph Johnson’s Confederates in North Carolina.

However, before joining Johnson, Lee had to supply and feed his roughly 57,000 men for their march south. Lee directed his subordinates to march their men toward Amelia Courthouse, where he hoped rations would be found.

After the Union breakthrough, Grant tried to block Lee from moving south. Grant’s forces closed in as Lee’s men struggled to find the supplies and rations they needed. Lee decided to move west toward Lynchburg, where he hoped to find the supplies his army needed. Mattocks and the men of the 17th Maine assisted in the pursuit of Lee’s forces. On April 3, after having marched 20 miles in a day, Mattocks wrote that his men were in good spirits and hoped for a quick end to hostilities.

Union cavalry attacks slowed the Confederates, and Union infantry under the command of generals Wright and Humphreys exploited a gap formed in the Confederate lines of march, forcing a series of engagements on April 6 known as the Battle of Sailor’s Creek.

After passing Amelia Springs, the 17th Maine, part of Humphrey’s Second Corps, formed for battle. The regiment encountered rebel fire from behind a line of breastworks. Seeing a ridge ahead with buildings to provide cover, the regiment took possession of this area and began firing into the Confederates. Major Mattocks then led a charge on the breastworks, shouting, “Give me the flag… All who will, follow me.”

The regiment pushed ahead, capturing more than a hundred Confederates and two flags.

Mattocks wrote in his journal afterwards, “I had, as usual, some warm escapes, but, as usual escaped without a scratch.” Despite Mattock’s luck, the regiment’s casualties were heavy, especially among the officers.

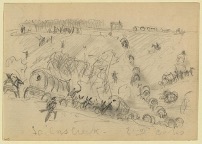

The rebel wagon train was just a few miles away, and the command was ordered to advance. Mattocks’ own horse, Charley, had become unmanageable when the battle began, so he rode the horse of his wounded lieutenant colonel to lead the attack. A quarter-mile away from the wagon train, the regiment took cover around several buildings, exchanging fire with the enemy. The regiment then received orders to charge the wagon train. At the wagon train itself, they captured a piece of artillery and about 50 prisoners. The remaining Confederates fled to safety.

Edwin B. Houghton, an officer in the regiment and the author of the 17th’s 1866 regimental history, wrote of the dilapidated state of the Confederate wagon train, remarking that “the enemy left in such a haste that many of the poor horses were still in harnesses… the [Confederate] wounded still remained in the ambulances, and many of the poor fellows had been a second time wounded during the engagement.”

All told, one officer and four enlisted men in the regiment were killed, with four officers and 23 enlisted men wounded. In May 1865, the regiment’s Corporal Asbury F. Haynes received a Medal of Honor for the capture of a rebel flag.

Among the wagons were officers’ dress uniforms, books, swords, and shotguns, which some of the men took as souvenirs and trophies of war. Mattocks obtained a General Orders book of Confederate general James Longstreet, an English-made double-barrel shotgun, and a silver-plated horse bridle. Confederates under Gordon were able to break free of the Union pincers but left many supplies in Union hands. As Lee rode east, he became aware of the disaster that befell his army, exclaiming, “My God! Has the army dissolved?” Meanwhile, Sheridan sent a report to Grant suggesting, “If the thing is pressed, I think Lee will surrender.”

Three days later, Mattocks wrote about receiving news of Lee’s surrender, “Cheer after cheer went up, and speeches were made… It is glorious to have served with the Army for these ten days! I am thankful that I got back in time for the funeral!” On April 12, Mattocks’ former professor and now general, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, presided over the formal surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia. In 1893, Chamberlain was awarded the Medal of Honor for his defense of Little Round Top at Gettysburg.

Major Mattocks, realizing the exemplary conduct of the 17th in their last campaign, issued congratulatory orders to the regiment on April 22 while camped at Burkesville, Virginia. He noted their gallant conduct and also their sacrifices, writing, “But while we rejoice over our success, let us remember that it was gained with the loss of valuable lives. If this is to be, as I trust it is, your last fight, all can remember it with pride and heartfelt satisfaction.”

Breveted a colonel at the close of the war, Mattocks mustered out on June 4, 1865. He entered law school, married, and was active in Union veteran organizations in the decades after the war. He was commissioned a brigadier general of volunteers during the Spanish American War, and in 1899 received the Medal of Honor for his actions at Sailor’s Creek. His citation concisely reads, “Displayed extraordinary gallantry in leading a charge of his regiment which resulted in the capture of a large number of prisoners and a stand of colors.”