On April 9, 1914, Mexican officials arrested nine U.S. sailors who had strayed into restricted space in the small oil town of Tampico. This set off a diplomatic crisis between Mexico and the United States that became known as the Tampico Affair. It seemed minor enough at first. Mexican authorities apologized but refused to salute the American flag on their own territory—both conditions demanded by the local U.S. naval commander, Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo. President Woodrow Wilson, however—generally regarded as a neo-pacifist—chose to escalate the crisis by ordering preparations for the military occupation of the Mexican port of Veracruz. He even pre-empted Congress by ordering operations to begin before permission arrived from Capitol Hill.

Wilson’s pretext for this operation, which seemed more pertinent to his predecessor Theodore Roosevelt’s “Big Stick” diplomacy, was the imminent arrival of an arms shipment in the port for the use of Mexican President Victoriano Huerta, generally considered an enemy of the United States. Ironically, the arms originated from an American businessman and a Russian arms dealer using a German-registered ship, the SS Ypiranga. But no matter—there were bigger issues at stake. The occupation of Veracruz commenced on April 21, 1914, and the arms were simply landed at another port a short time later.

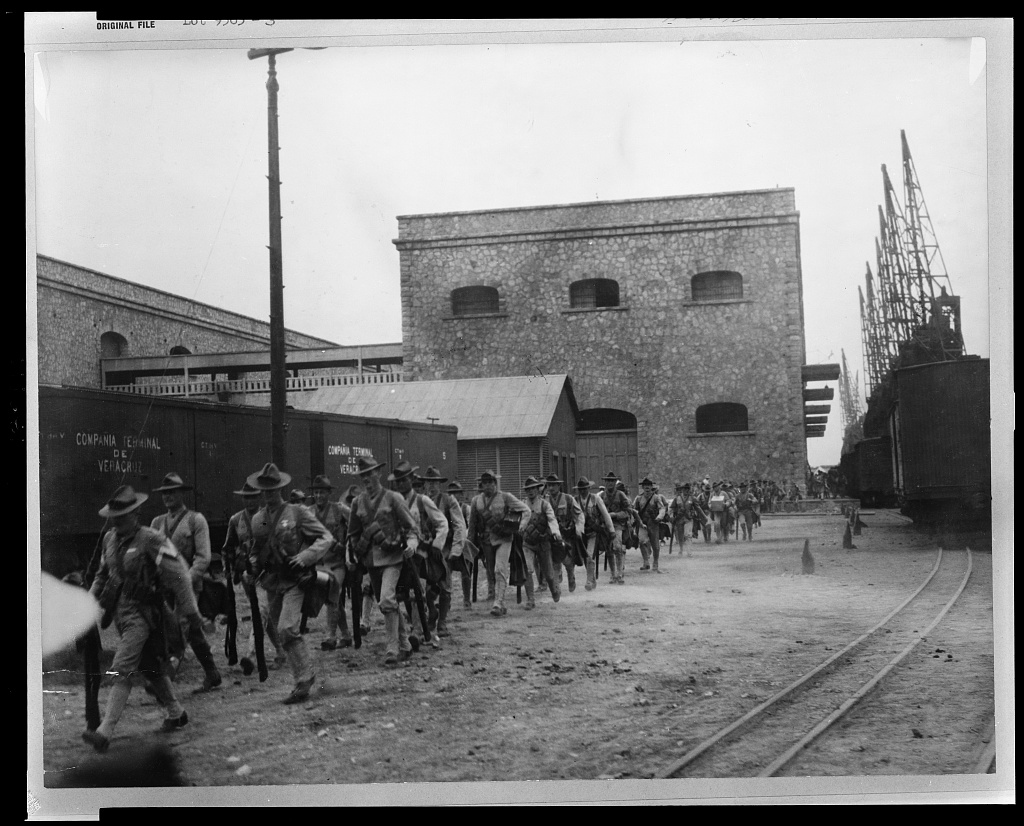

The invasion force, dispatched from U.S. Navy warships already offshore under the command of Rear Admiral Frank F. Fletcher, consisted of several Marine detachments including the 2nd Advanced Base Regiment and some armed sailors, amounting in total to several hundred men. Although the Americans did not at first encounter organized resistance as they moved to occupy the port, Mexican regular army detachments and even some naval cadets began fighting back over the course of the afternoon. The Mexicans fought fiercely despite a lack of central command, and for a time they set the Americans back on their heels.

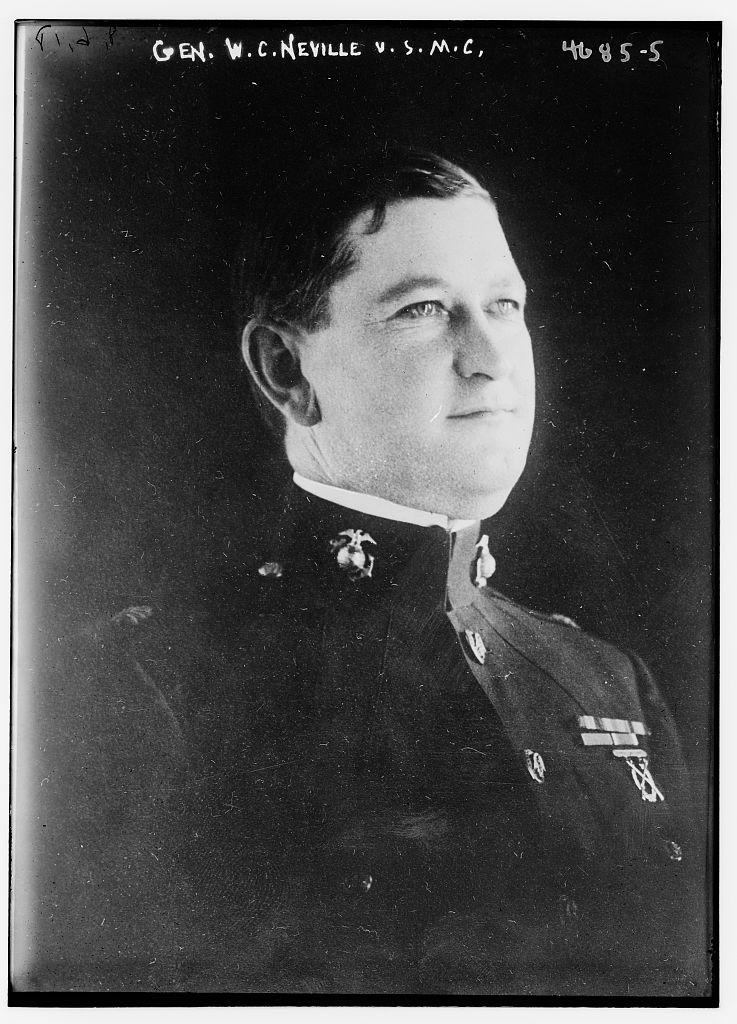

Many of the American participants in the ensuing battle, particularly Marines, would later become well known for their service in World War I. These included the commander of the 2nd Advanced Base Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Wendell Neville. As they attempted to occupy the rail yards, the Marines encountered increasingly stubborn resistance not just from uniformed Mexican servicemen but from armed civilians and even prisoners released by the authorities from the city jail. Neville was among those who would receive the Medal of Honor in the ensuing action, which ended with the Marines and sailors—the latter reinforced by almost 400 men from the fleet—taking control of all of their objectives by the end of the afternoon.

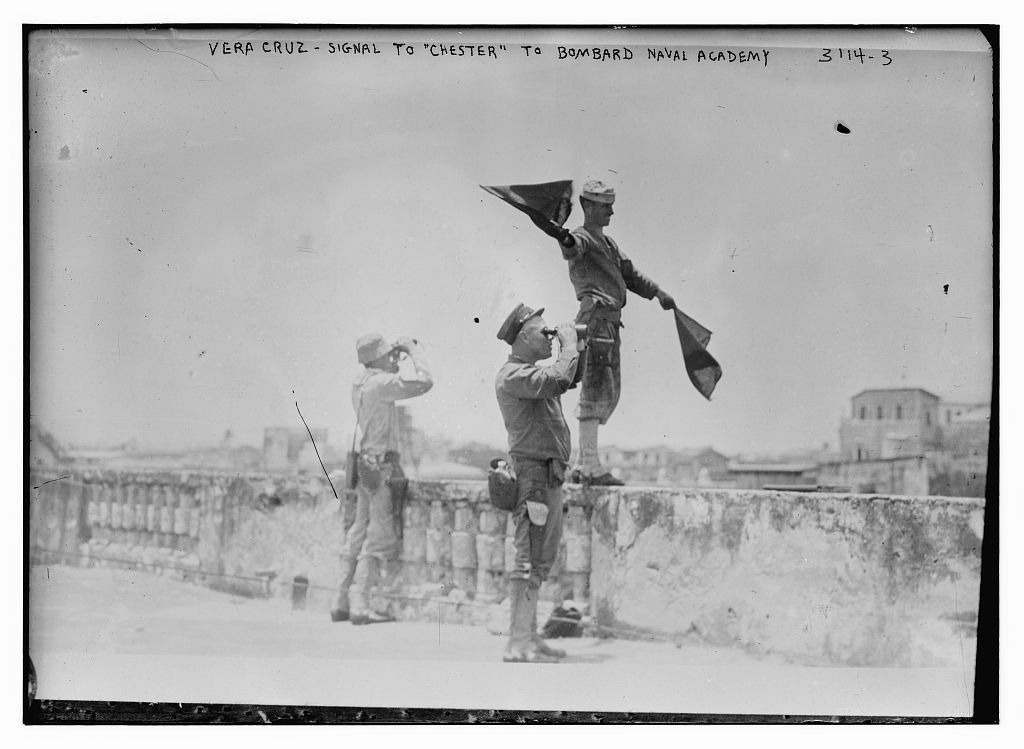

American control was tenuous, however, and faced increasing public scrutiny. Sensing the danger of simply holding his meager forces along the waterfront, on April 22 Admiral Fletcher deployed a Marine battalion that had just been brought up from Panama along with several hundred more sailors from an offshore fleet that now included several battleships. He then ordered them to occupy the entire city of Veracruz. The ensuing street fighting marked an interesting prelude to what U.S. Armed Forces would undertake in Germany, Vietnam, and Iraq several decades later, but at the time it was all new to the untried Americans. Combat centered around the Mexican Naval Academy, where U.S. sailors took severe casualties before American battleships pummeled the defenders into submission—in the process reducing the academy to ruins. Colonel John A. Lejeune subsequently led the Marine 1st Advance Base Regiment ashore, providing vital assistance to securing the city.

Captain Douglas MacArthur served as an intelligence officer during the occupation of Veracruz, which lasted until November. Although the Americans suffered fewer than 100 casualties against some 550 Mexican casualties, the affair was treated as a notable achievement of American arms, with Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels awarding an astonishing 56 Medals of Honor. Many Americans, including some of the recipients, angrily berated what they regarded as a cheapening of the award.

The occupation of Veracruz certainly had diplomatic consequences, incensing anti-American feeling throughout Latin America, and also helping Mexico tilt toward the pro-German camp during World War I. It also played an indirect role in fueling the Zimmermann Telegram fiasco of 1917. More broadly, Veracruz marked one further episode in the chaotic and bloody Mexican Civil War, which again generated American intervention along the border in 1916.