By Edward G. Lengel, Ph.D.

Alvin Cullum York’s character didn’t amount to much—at least, not early on. Born on December 13, 1887, near the small town of Pall Mall, Tennessee, he grew up in the beautiful but lonely hills of the Upper Cumberland along the Kentucky border. His parents were poor farmers like most of the other folks in those parts, and Alvin was the third of eleven children who had to squeeze into the family’s one-room cabin. Although he worked hard on the farm, and became an expert huntsman, as a teenager Alvin fell in with a bad crowd. In common with other restless young men with little to hope for but hardscrabble farming, York drank, cussed, and got into fights—and only went to church out of a sense of duty to his parents.

That was before he met Gracie Loretta Williams. With her big blue eyes, blond hair, and graceful demeanor, Gracie bewitched Alvin and it was not long before he began attending church regularly just so that he could meet her. But Gracie’s standards were high, and so were her parents’. No rowdy young man was going to court their daughter. Held at a distance, Alvin could only pine for the woman he loved. This painful refusal, combined with some ugly experiences in back-country drinking houses called “Blind Tigers,” convinced Alvin York to follow a new and better path.

In the Christmas season of 1914, York began attending a tent revival meeting run by Rev. Melvin Herbert Russell. “It was as if lightning struck my soul,” he recalled; and on New Year’s Day, 1915, while World War I raged in Europe, Alvin Cullum York stepped forward to accept Jesus Christ as his personal savior. Everyone could tell that York’s heart was changed, for he embraced his new creed with all his heart and mind. And so the path opened to Gracie’s heart as well. Allowed once more to court, they took a slow and gentle path toward union, and it was not until June 1917 that Gracie consented to be Alvin’s wife. By then, though, the United States had entered the war, with fateful consequences for this humble Tennessee farmer.

Uncertain whether the Bible permitted him to fight and possibly take another man’s life, York registered for the draft only reluctantly. And when his number was called, he sought exemption as a conscientious objector. Exemption was denied, however, and so Private York entered basic training with the 82nd “All American” Division. It wasn’t until March 1918, though, after study, prayer, and debate over the war’s purpose and the Bible’s meaning with some of his officers, that York finally decided that God would permit him to fight, and possibly kill, in service to his country. Returning home for one last visit before he shipped overseas, Alvin met Gracie in a country lane for one final embrace, both of their hearts breaking as they said goodbye.

Now-Corporal Alvin York’s “day of glory” came on October 8, 1918 when, with the assistance of several fellow Doughboys, he captured 132 German soldiers in France’s Argonne Forest. In the course of the action, he also killed up to two dozen German soldiers—some of them face to face, so that he could see their expressions as they died. During the fight, he acted automatically, making use of his prowess as a hunter; and afterwards he didn’t see anything very glorious about it. Far from feeling proud of what he had done, York was horrified and ridden with guilt—not just for the men he had killed, but for the comrades whose lives he had been unable to save. On the following day, he returned to the battlefield with two stretcher bearers, looking desperately for survivors. He found none.

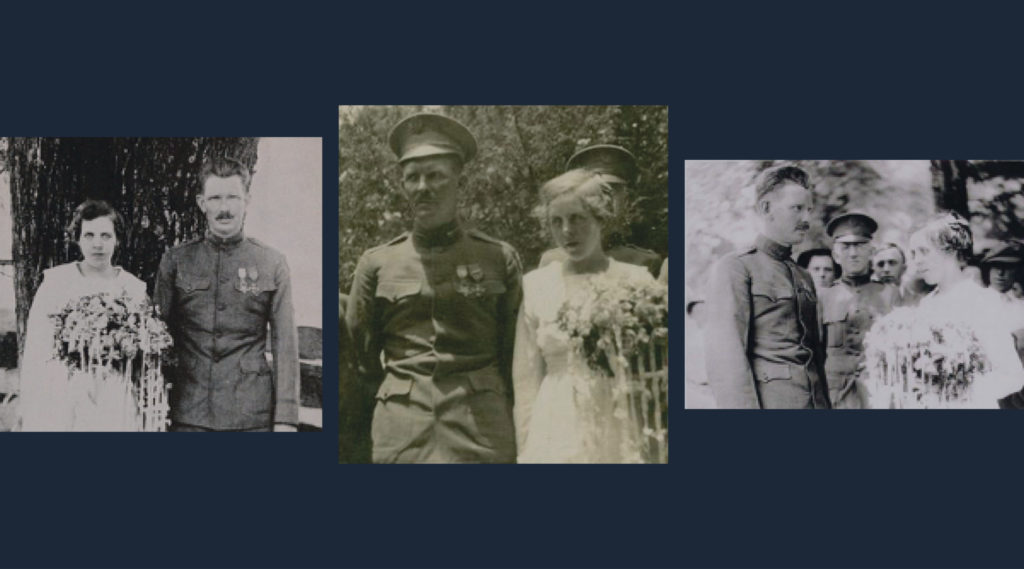

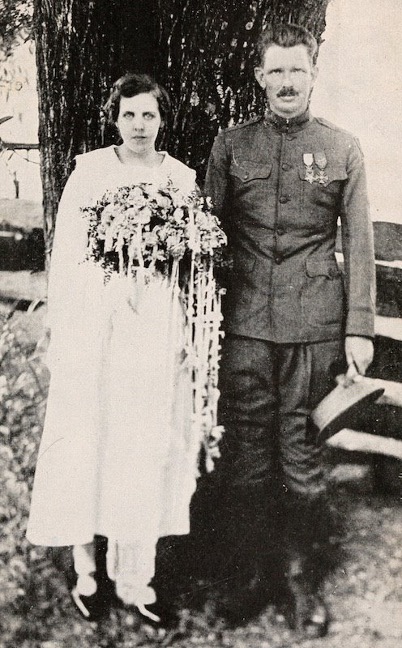

Promoted to Sergeant and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross shortly after the action, York was awarded the Medal of Honor in France on April 18, 1919. He returned the following month to the United States, where he was treated as a hero. But York’s mind thought only of home, and Gracie. “What Ah like best of all,” he told a reporter, “is just to get back. It’s where Ah’ve been all my life an Ah reckon it’s the best place for me.” At the end of May, York made his way back up to the hills of East Tennessee. And on June 7, 1919, two years since their engagement, and two years since Alvin had been drafted into military service, he and Gracie were married.

The wedding was performed by Tennessee Governor Albert H. Roberts, with the ceremonies taking place beneath a bower of pine trees. “There will be no wedding march,” it was announced, “save the wind in the pines.” Afterward, people came from the hills all around to celebrate with a “monster picnic dinner spread under the trees near York’s cabin home. For miles and miles up in the hills, some even from Kentucky, the people, old and young, have come, bringing their baskets well filled with chicken and hams and pies and cakes of a multitude of forms. . . . York and his bride . . . will be dined upon the best the Cumberland mountains afford and wined upon the crystal cold water of the gushing York spring.”

Gracie and Alvin’s marriage stood strong over the years to come, as he devoted himself to charity work and she helped soothe his haunting memories of the war. They had eight children, all of whom would emulate their parents in character, commitment, and service to their communities and to their country. Alvin, who died in 1964, and Gracie, who followed him in 1984, are buried side by side at the Wolf River Cemetery at Pall Mall, Tennessee, not far from the Alvin C. York State Historic Park that continues to pay tribute to his legacy.