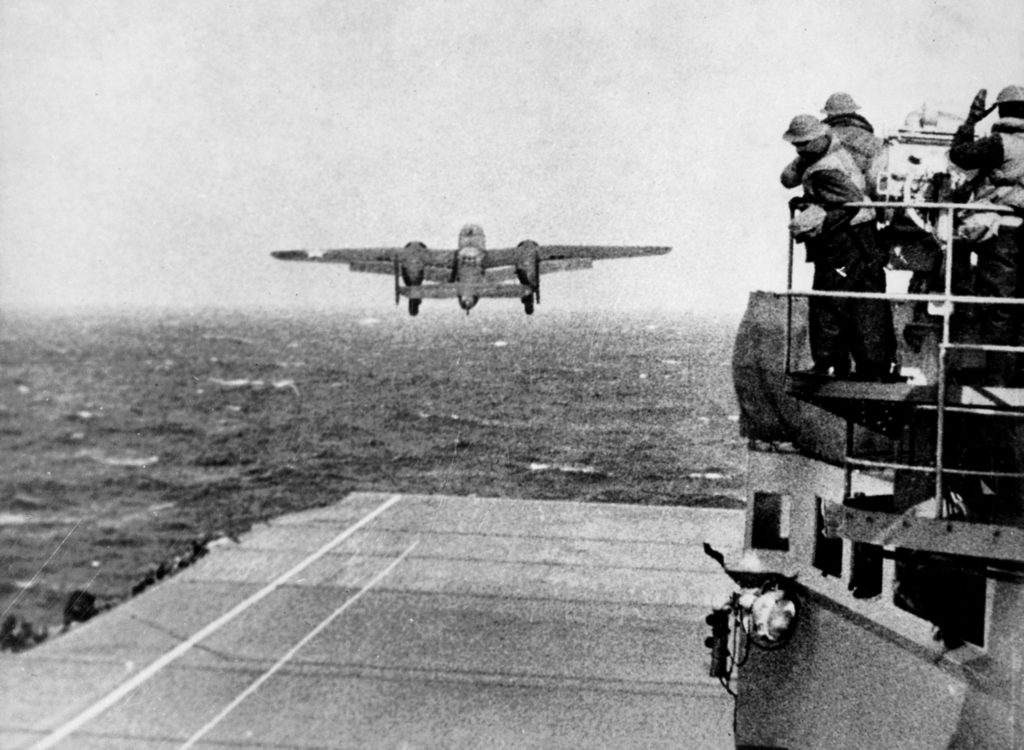

On the morning of April 18, 1942, eighty specially trained volunteer airmen climbed into sixteen B-25 bombers and set out for Tokyo, Japan in what became one of the most iconic missions of World War II. Almost immediately following the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, American officials recognized that a counterstrike on the Japanese Empire was crucial. The Doolittle Raid served as retaliation for the loss of life and property caused by the attack, and sought to bring the war home to Japan. The plan called for sixteen B-25s, each staffed by a five-man crew to launch from the Pacific Ocean off the deck of the U.S.S. Hornet. After completing the mission, the plan was to land the B-25s in China.

Preparing for the Raid

Leading the men was Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle. Under his command, the raid needed enough pilots, bombardiers, and gunners to operate all sixteen of the B-25s. Officials determined that that the Seventeenth Bombardment Group could spare the planes needed for the mission and Doolittle, not wanting to leave aircrews without their aircraft, chose to recruit for the mission from the same group. The men who were selected by Doolittle reflected a cross section of the nation they were serving. They came from small towns and large cities, from the North, South, West, and East regions of the United States. Some were the sons of new immigrants while others came from families with deep American roots. All carried with them a sense of duty.

To prepare for the raid, the planes had to be modified to carry extra fuel tanks for the long journey. They were assembled at Eglin Field in Florida, where the crews practiced their secret and risky mission taking off from a 750-foot runway. Once their training was completed, the crew moved on to McClellan Field in Sacramento, California where the planes received final modifications. The stress of the dangerous operation weighed heavily on all the men, and pilot Vernon Stintzi even developed an ulcer. When Stintzi was relieved of flying duty, Doolittle took the opportunity to serve in his place.

Taking Flight

On April 1st the planes were loaded on to the U.S.S. Hornet at Alameda, California, the same town where James Doolittle was born in 1896. The men and the planes had a long journey across the Pacific Ocean before they could begin their mission. In the early morning of April 18, 1942, the airmen boarded their aircraft on the deck of the U.S.S. Hornet and prepared to take flight for Tokyo, Japan.

All sixteen planes successfully launched from the U.S.S. Hornet, headed for their targets. The airmen bombed ten targets in Tokyo, two in Yokohama, and one in Yokosuka, Nagoya, Kobe, and Osaka. After completing their mission, the plan called for the airmen to head towards China where they were supposed to land on the designated bases. However, several factors contributed to the planes not reaching their intended landings, most notably the rapidly changing weather and the low fuel in the planes. Instead, fifteen crews either crash landed or bailed out of their planes. The sixteenth had a dangerously low amount of fuel after the bombings and, rather than risk crashing in the East China Sea, the crew landed in the Soviet Union.

Of the crews that reached China, three airmen were killed during the crash landings. Two of the crews were captured by Japanese forces in China; of those captured, four of the airmen remained prisoners until the end of the war, three were executed by the Japanese, and one died of dysentery. The crew that landed in the Soviet Union was held by the Soviets for over a year in various locations around the country. Of the eighty men who boarded the planes on April 18th, only sixty-one survived the war. All sixteen planes used for the Doolittle Raid were either destroyed or lost.

Doolittle and the Medal of Honor

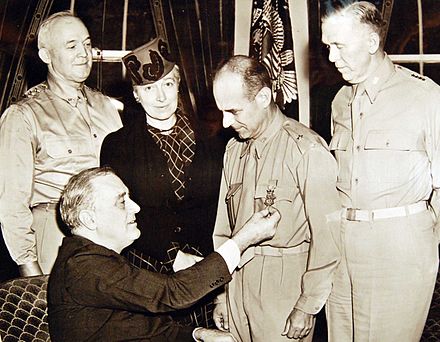

Doolittle, the man who orchestrated and led the bombings, later wrote that, upon crashing, he was concerned that the mission had been a failure. Further, Doolittle feared that he would be court martialed upon arriving back to the United States as he had launched the attack early after being spotted by a Japanese vessel, and had lost all sixteen of the B-25s. When Doolittle arrived back in the United States on May 18th, he was taken directly to the War Department in Washington, D.C. Unbeknownst to him, his wife, Josephine Doolittle, had flown across the country to meet him. On May 20th a car with General Henry Arnold and General George Marshall arrived to pick up Doolittle. As they began driving, the two informed Doolittle that he was headed to the White House to receive the Medal of Honor.

On May 20, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt presented the Medal of Honor to General James Doolittle. The citation for the medal read, “For conspicuous leadership above the call of duty, involving personal valor and intrepidity at an extreme hazard to life. With the apparent certainty of being forced to land in enemy territory or to perish at sea, Gen. Doolittle personally led a squadron of Army bombers, manned by volunteer crews, in a highly destructive raid on the Japanese mainland.”

Doolittle planned and personally led a daring and treacherous daylight raid on Japan in full view of the enemy. The Doolittle Raid did little physical damage; however, it significantly bolstered American morale in the wake of Pearl Harbor and directly struck at Japan’s homeland. Medal of Honor recipient James Doolittle continued to serve throughout the rest of World War II. After the war he worked as the Vice President of Shell Oil while simultaneously serving in the Air Force Reserve. He formally retired from the military in 1959 and in April 1985 he was promoted to the rank of four-star general. General James Doolittle passed away on September 27, 1993, at the age of 96. He is interred at Arlington National Cemetery outside of Washington, D.C.

For further reading on the Doolittle Raid, see James Scott’s Target Tokyo: Jimmy Doolittle and the Raid that Avenged Pearl Harbor.