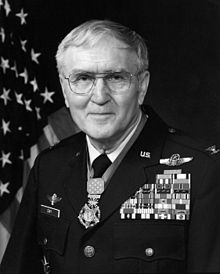

- Recipient: George “Bud” Day

- Branch: U.S. Air Force

- Combat: Vietnam

Home isn’t where we live. It’s the people we spend time with. But what happens when we’re away from home for an extended period of time? We fight hard to get back, which is exactly what Medal of Honor recipient George “Bud” Day did.

Day was born on February 24, 1925, in Sioux City, Iowa. Growing up, Day enjoyed playing basketball, and he often played with friends outside the home of his future wife and high school sweetheart, Doris Sorenson. While the boys played, 9-year-old Doris would bring them water.

In 1942, 17-year-old Day entered the U.S. Marine Corps, serving as a gun battery on Johnson Island in the Pacific for two years. He and Doris began dating shortly after he returned home from World War II, and he enjoyed attending church on Sundays with her family. Day was a shrewd scholar, and he earned a law degree from the University of South Dakota School of Law.

By 1950, Day was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Iowa Air National Guard. A year later, he received a call to active duty and earned his wings in 1952. Day flew two tours as an F-84 Thunderjet pilot in the Korean War. Following the conflict, he continued serving in the Air Force until the early 1960s. In 1967, Day, then 43, volunteered to serve in Vietnam. He left his family on March 26 of that year. After some time in the country, he was recruited to command a new unit. He named it “Misty” after his favorite song. Little did he know that it would be the last time he’d be on American soil—much less at home—for five years, seven months, and 13 days.

A Five-Year Delay

On August 26, 1967, while then Major Day was flying an F-100 Super Sabre during a combat mission, his aircraft was shot down over North Vietnam, forcing him to eject. Upon landing, it was evident that he had broken his right arm in three places and had a significant left knee sprain. He was quickly captured, beaten, and tortured at an enemy prison camp. Five days later, Day escaped and headed toward the Marine base at Con Thien in South Vietnam. He journeyed about 25 miles without boots, surviving on wild berries and raw frogs. After 10 days, Day crossed the Ben Hai River, using a bamboo log as a floating device. Despite signaling to U.S. aircraft for help, he was shot in the left hand and thigh and subsequently recaptured by the Viet Cong. Day was taken back to his original prison camp, then moved to the “Hanoi Hilton,” as it was called by POWs.

Back at home, Doris was busy raising the four Day children: two sons, Steve and George Jr., and twin girls, Sandra and Sonja. She quickly learned to rely on her eldest son, Steve, who became her strength and accepted the responsibilities as “man of the house” while his father was away.

In her husband’s absence, Doris was extremely active in POW organizations. She served as the Phoenix area chair of the Prisoner of War Wives and Missing in Action Wives group and the area coordinator of the National League of Families of American Prisoners in Southeast Asia. And she never stopped praying for and believing in Day’s safe return.

At Hanoi, Day continued resisting enemy attempts to get military information through torture, beatings, and interrogation. Day and other POWs sang the national anthem with rifles pointed in their faces. When American bombing crews completed Operation Linebacker II and POWs began celebrating, Day urged them to sit quietly after noticing enemy weapons in the prison windows. “People started clapping, cheering, and screaming,” Day recalled, according to an article from the Medal of Honor Museum. “All of a sudden, there were a bunch of Vietnamese with automatic weapons … I said to everyone, ‘Sit down. This is not the time for somebody to be killed.’”

An Honorable Homecoming

On March 14, 1973, Day was released along with 108 other American POWs. Three days later, he reunited with Doris and his children at March Air Force Base in California. Doris recounted the story to NWF Daily News, saying, “That was the happiest day of my life. We just couldn’t stop talking and he had missed so much.” Day’s deliverance was part of Operation Homecoming, which organized the release and return of 591 American POWs during the Vietnam War.

For his incredible gallantry, remarkable bravery, and unshakeable integrity, Day earned the Medal of Honor. He accepted the Medal from President Gerald Ford during a White House Ceremony on March 4, 1976, along with three other service members.

Day was highly respected by his peers. The late former Senator John McCain III, who was Day’s cellmate in North Vietnam, said this about him: “I owe my life to Bud, and much of what I know about character and patriotism…. He was the bravest man I ever knew, and his fierce resistance and resolute leadership set the example for us in prison of how to return with honor.”

Day is the only man to earn both the Medal of Honor and the Air Force Cross for his acts of valor and heroism. With more than 70 decorations, he is widely considered the most decorated officer in United States Air Force history.

A Fight for Honorable Rights

Day retired from the Air Force in 1977, but he wasn’t done yet. He wrote two autobiographies and set up his own law practice. Day spent much of his time advocating for veterans and ensuring they received necessary medical benefits after returning home from combat. In 1996, he told Doris he was going to sue the federal government because it wasn’t providing veterans with the healthcare benefits it had promised. She thought he was crazy. Although Day’s case reached the Supreme Court five years later, the justices did not take it. However, Day’s efforts were enough to rattle lobbyists and politicians in Washington, D.C. He is credited with passing the TRICARE for Life Act, which supports healthcare access for retired military service members.

“No one had more guts than Bud or greater determination to do his duty and then some — to keep faith with his country and his comrades whatever the cost. Bud was my commanding officer; but more, he was my inspiration — as he was for all the men who were privileged to serve under him,” the late Senator McCain recalled.

Day died July 23, 2013, at his home in Florida, surrounded by his children, grandchildren, and loving wife, Doris. His steadfast commitment and actionable integrity in the face of indescribable adversity is what makes him such a memorable and iconic American hero.