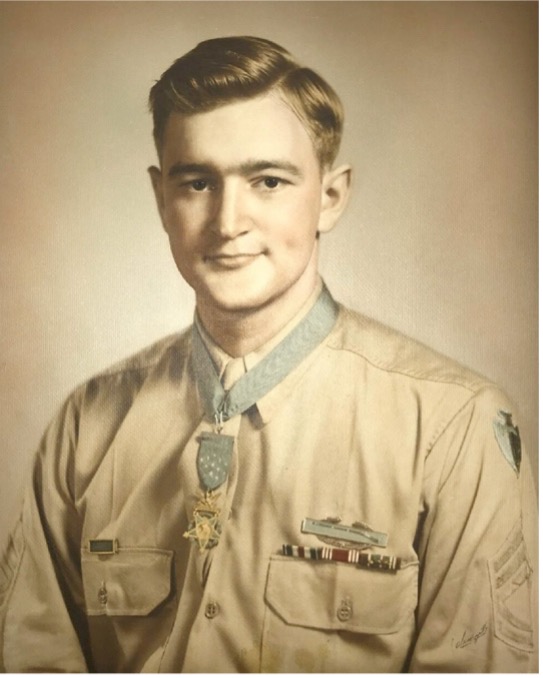

Technical Sergeant Charles Henry Coolidge earned the Medal of Honor in 1944 for his heroic conduct during the U.S. Army’s epic struggle to capture heavily defended German positions in the Vosges Mountains region in eastern France. Over the course of four harrowing days from October 24-27, 1944, Coolidge, serving with the 36th “Texas” Division’s 141st Infantry Regiment, led a determined but inexperienced American infantry in a mission to support their battalion’s right flank against strong enemy forces. Then, with no officers present, Coolidge stood firm in beating back repeated German attacks backed by armor, frequently exposing himself to enemy fire and even advancing into the teeth of enemy assaults to break them up with hand grenades. Finally, facing overwhelming odds, Coolidge directed a tactical withdrawal, preventing what might have become a rout and saving many of his men’s lives. He was the last to leave his position. For these actions, Coolidge was awarded the Medal of Honor on June 18, 1945.

On Tuesday, April 6, 2021, Charles Henry Coolidge passed away at the age of ninety-nine.

Biographical Information:

Rank at Time of Action: Technical Sergeant

Highest Rank: Technical Sergeant

Service: US Army

Birthday: August 4, 1921

Place of Birth: Signal Mountain, TN

Unit: 2nd Platoon, Company M, 3rd Battalion, 141st Infantry, 36th Infantry Division

Date of Action: 24-27 October 1944

Place of Action: East of Belmont sur Buttant, France

Leading a section of heavy machine guns supported by one platoon of Company K, he took a position near Hill 623, east of Belmont-sur-Buttant, France, 24 October 1944, with the mission of covering the right flank of the 3d Battalion and supporting its action. TSgt. Coolidge went forward with a sergeant of Company K to reconnoiter positions for coordinating the fires of the light and heavy machine guns. They ran into an enemy force in the woods estimated to be an infantry company. TSgt. Coolidge, attempting to bluff the Germans by a show of assurance and boldness, called upon them to surrender, whereupon the enemy opened fire. With his carbine, TSgt. Coolidge wounded two of them. There being no officer present with the force, TSgt. Coolidge at once assumed command. Many of the men were replacements recently arrived; this was their first experience under fire. TSgt. Coolidge, unmindful of the enemy fire delivered at close range, walked along the position, calming and encouraging his men and directing their fire. The attack was thrown back. Through 24 and 26 October the enemy launched repeated attacks against the position of this combat group but each was repulsed due to TSgt. Coolidge’s able leadership. On 27 October, German infantry, supported by two tanks, made a determined attack on the position. The area was swept by enemy small-arms, machine-gun, and tank fire. TSgt. Coolidge armed himself with a bazooka and advanced within 25 yards of the tanks. His bazooka failed to function and he threw it aside. Securing all the hand grenades he could carry, he crawled forward and inflicted heavy casualties on the advancing enemy. Finally it became apparent that the enemy, in greatly superior force, supported by tanks, would overrun the position. TSgt. Coolidge, displaying great coolness and courage, directed and conducted an orderly withdrawal, being himself the last to leave the position. As a result of TSgt. Coolidge’s heroic and superior leadership, the mission of his combat group was accomplished throughout four days of continuous fighting against numerically superior enemy troops in rain and cold and amid dense woods.

The Story of Charles Henry Coolidge

Born on August 4, 1921, near the small town of Signal Mountain, just north of Chattanooga in southeastern Tennessee, Charles Henry Coolidge grew up in the vicinity of several Civil War battlefields that included the sites of numerous Medal of Honor-awarded actions. As a child, Charles suffered from a severe speech impediment that made him the butt of schoolyard jokes, and he spent several years learning patience and diligence while working with a family friend who tutored him until he could communicate effectively.

Charles Coolidge’s father, Walter, owned and ran a small printing company that would be passed down from generation to generation through the family, and imbued his son with a strong sense of ethics and responsibility. During the trying years of the Great Depression through the 1930s, Walter Coolidge pinched pennies so that he could avoid laying off a single one of his employees, providing them with just enough income so that they could care for their families. This commitment to caring for the less fortunate impressed itself deeply on young Charles, who worked for the family business as a teenager while he attended Chattanooga High School, from which he graduated in 1939.

For the next two years, Charles Coolidge applied himself to the family business and became a master bookbinder—a profession he would pursue for the remainder of his working life. On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and the United States entered World War II. Coolidge had never heard of Pearl Harbor before, but he had expected for a long time that America would get involved in the war and that he would have to fight. When someone asked him back in 1939 why he didn’t go to college, eighteen-year-old Coolidge quipped, “It don’t take any smart individual to go over there and shoot Germans!” Still, Coolidge did not enter service until he was drafted into the U.S. Army in June 1942, and went for basic training to Fort McClellan, Alabama.

In basic training, Coolidge received the only wound of his military life as he accidentally cut his own leg badly with a bayonet. His officers thought at first he was malingering in order to get out of combat service, but changed their minds as the infection got so bad they nearly had to amputate his leg. Back in training after his recovery, Coolidge dedicated himself to becoming an effective soldier, but also pitched softball games, a talent that would come in handy with grenades later on. In November 1942 he was sent to Camp Edwards, Massachusetts, and assigned to Company M, 3rd Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th Infantry Division, a formation that originated in the Texas National Guard.

In April 1943, Coolidge shipped off to North Africa with his unit. In September of that year his unit landed near Paestum in southern Italy, with the 36th Division being the first American division to land on the continent of Europe. Coolidge saw combat for the first time during the Battle of Salerno. Coming under fire tested his resolve, and he passed with flying colors. “Patton says anybody that says he was not scared in war is a liar,” he later remembered. “Well, maybe I was, but I never knew it if I was.” Advancing up the “boot” of Italy, with brutal fighting at the crossing of the Rapido River and then in the breakout from Anzio to Rome in 1943-1944, Coolidge was involved in combat repeatedly, earning the Bronze Star and Silver Star. Asked about his actions later, though, he was typically humble, claiming not even to know what he received the first decoration for, and characterizing the second as just a “little battle.” Many around him were killed, however, and his entire company was destroyed in the crossing of the Rapido. “If you got across,” he later recalled, “very, very few ever got back. And the ones that got back were by miracles.”

The Medal of Honor

In August 1944 the “Texas” Division landed in southern France as part of Operation Dragoon. The advance toward the French border with Germany was a “picnic” for Coolidge and his men as enemy resistance melted away—until they reached the Vosges Mountains. There, on October 22, Coolidge led twenty-seven men up an eminence called Hill 623. German troops occupied a heavily wooded hill nearby, and applied constant pressure on the Americans, partly to prevent them from linking with the 141st Regiment’s 1st Battalion—the “Lost Battalion”—which became cut off and surrounded a short distance away on October 24.

Coolidge’s orders were to hold the hill—and he did. Over the next few days the Germans launched repeated attacks, sometimes backed by tanks and often by artillery, but the beleaguered Americans, inspired by Coolidge’s example, always hurled them back. After its heavy losses of the previous months, Company M was filled with large numbers of inexperienced and skittish replacements, and they relied heavily on Coolidge to keep them fighting.

On the morning of October 27, finally, the Germans launched an overwhelming attack backed by armor. At one point, a German tank drove up next to Coolidge’s machine gun position. Poking his head out of the turret hatch, the tank commander turned to Coolidge and said, in perfect English, “Do you guys want to give up?” “I’m sorry Mac,” the American coolly replied, “you’ve got to come and get me!” Enraged, the German closed the hatch, and the tank’s main gun opened fire on Coolidge several times at practically point blank range as he ran from tree to tree. But he was never injured, and after the bazooka that he trained on the German tank failed to operate, he continued throwing grenades at the enemy infantry until it became necessary to withdraw. And Coolidge was the last man down the hill.

After this engagement, Coolidge remained in combat with his division as it fought through the Vosges Mountains and into Germany in 1944-1945. All along the way, he took one day at a time. With each battle, “I just said, ‘Well we got to do it, let’s do it now,’” he recalled in an interview. “Tomorrow never comes, today’s the only day you got to live. Tomorrow will still be tomorrow.” It was his deep religious faith, though, that shielded Coolidge from fear and, he believed, from harm. “Anything I did do during the war,” he said, “I give God the credit. I mean Jesus walked with me every step of the way. . . . I would go anywhere, do anything, never worried that they were shootin’ at me. I still stay the Lord must’ve curved many a bullet that I knew absolutely they were shooting at me.” But his main devotion was to others. Above all, “I didn’t care about me. I cared about my men. I’d do anything for them.”

After receiving the Medal of Honor in Germany on June 18, 1945, Coolidge returned to the United States and his home on Signal Mountain, where he spent the rest of his life. In 1966, he began showing symptoms of Multiple Sclerosis, and its effects intensified as the years passed. In combating the illness, he showed the same dedication, calmness, deep faith, and good humor that had motivated him during the war. Despite this, and his preference to avoid publicity, Coolidge understood the continuing importance of his example to others and was a dedicated member of his community. His final act of service was establishing the Charles H. Coolidge National Medal of Honor Heritage Center in Chattanooga, Tennessee, which pays tribute to his legacy by educating and inspiring generations now and to come.

Learn More About Charles Henry Coolidge:

- Charles H. Coolidge National Medal of Honor Heritage Center

- The Hero of Signal Mountain

- Interview (2010) with Charles Coolidge for the Veterans’ Oral History Project

- Full Coolidge interview by LOC

Media

Chattanooga Daily Times: Sgt. Coolidge Coming Home Soon; Is Decorated With Medal of Honor

T/Sgt. Charles Henry Coolidge, Chattanooga’s only winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor, is coming home soon, he has cabled his parents from Austria. Yesterday Mr. and Mrs. Walter P. Coolidge of Signal Mountain received the following message: “Was decorated June 18 at regimental review. Very proud of award. Expect to be home soon. Love. Charles.” (June 24, 1945, Page 3)