Determined to Serve

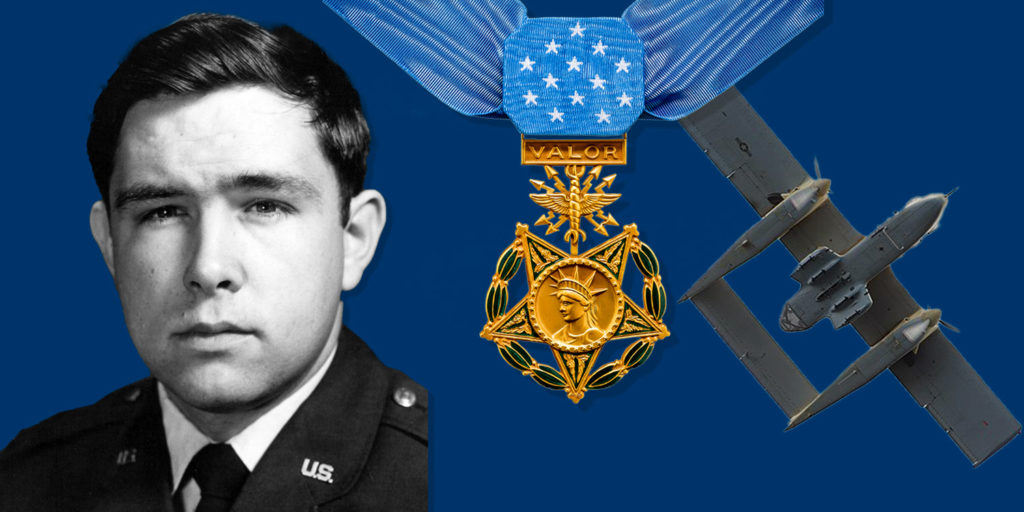

Born in Palestine, Texas, in 1946, a young Steven Bennett later moved with his family to Louisiana. Bennett graduated from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (then University of Southwestern Louisiana) in 1965 with a degree in Aerospace Engineering. As an ROTC graduate with a pilot’s license, Bennett entered the U.S. Air Force in August 1968 and earned his silver pilot’s wings in 1969. Steven, when he was getting ready to propose marriage to his future wife Linda, told her that with him it would always be “God, Country, and then family in that order.”

Bennett first learned to fly the B-52 Stratofortress strategic bomber and flew missions out of Thailand before transitioning to become a Forward Air Controller (FAC). Despite the significant drawdown of U.S. forces in Vietnam and the surging unpopularity of the conflict, Bennett was determined to keep serving in a combat capacity. Bennett requested a tour in Vietnam and was subsequently assigned to the 20th Tactical Air Support Squadron, flying North American OV-10A Broncos from the airbase at Da Nang.

The 1972 Easter Offensive

Under President Richard Nixon’s “Vietnamization” strategy, U.S. combat forces had been largely removed from Vietnam and combat duties had been handed over to the South Vietnamese military. To support their allies in 1972, the U.S. retained a small cadre of military advisors embedded with South Vietnamese units and aviation and naval assets, which would help check any North Vietnamese Army (NVA) attacks.

With the American forces now largely absent from the theater, the North Vietnamese Army sensed an opportunity and launched its 1972 Easter Offensive against South Vietnam. Bennett and the other members of the 20th Tactical Air Support Squadron (20th TASS) flew an increasing number of support missions, helping direct artillery and naval gunfire against NVA forces.

Broncos and Strelas

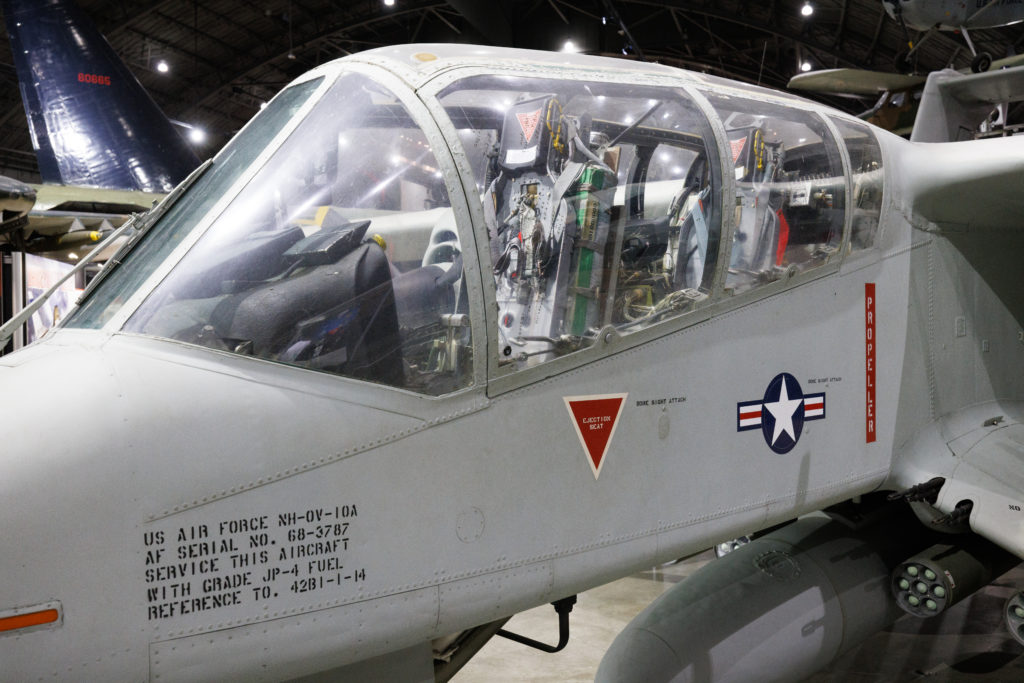

The North American OV-10A Bronco was an excellent aircraft for the FAC mission that Bennett was assigned to fly. The lightweight, two-seat, twin-turboprop plane could carry a relatively large amount of ordnance, and its big bubble canopy afforded excellent visibility forward and to the sides. Despite being an effective and popular plane to fly, the Bronco did have one disadvantage over the other light observation aircraft flown by the 20th TASS – its two larger engines generated far more heat. And that larger heat signature made the Bronco more vulnerable to a new and growing threat in Vietnam – the SA-7 Strela (Grail) surface-to-air missile. The SA-7 was the Soviet Union’s first credible shoulder-fired heat-seeking surface-to-air missile, and the North Vietnamese Army had begun to use these highly portable missiles to defend against U.S. and South Vietnamese air attacks. Because of this new threat, OV-10 Broncos were forced to fly higher and were discouraged from making repeated passes over NVA units.

Covey 87 and Wolfman 45

Around 3 pm on June 29, 1972, Steven Bennett, call sign Covey 87, and his backseater, Marine Captain Mike Brown, call sign Wolfman 45, took off from Da Nang to fly a support mission. Brown’s role in the backseat was to coordinate naval gunfire support from the U.S. destroyer USS Richard B. Anderson (DD-786) and cruiser USS Newport News (CA-148) off the coast of Vietnam.

Three hours into their uneventful mission and getting ready to return to base, Bennett and Brown received an urgent call from a US Marine artillery spotter embedded with a platoon of South Vietnamese marines near Quang Tri City. This small group of around 24 marines was in danger of being overwhelmed by hundreds of NVA regulars supported by heavy artillery. Without immediate support from artillery or airstrikes, it was almost certain that this unit would be destroyed.

Per their role as a Forward Air Controller, Bennett got on the radio and requested close air support strikes against the NVA forces but learned that no strike aircraft were available. Brown, expert in calling in naval gunfire, also determined that the big Navy guns were as likely to hit friendly forces as they would the enemy given the proximity of the two forces.

Commitment: Bennett Attacks

With no other options available and time running out, Bennett radioed his command for approval to attack the NVA forces with his Bronco. Armed with just four 7.62mm M60C machine guns in the stubby winglets under the twin cockpits, Bennett needed to descend to a lower altitude that would expose his aircraft to light arms fire and the deadly SA-7s.

Given approval, Bennett rolled his plane into a steep dive and lined up the Bronco’s gunsights on a line of trees near a creek bed where many of the NVA soldiers had gathered. Bennett’s guns laced the tree line with deadly fire. Zooming back up to altitude, Bennett’s Bronco had taken a few hits from small-caliber enemy fire but was still in good shape. Not wanting the NVA to regroup from his first attack, Bennett lined up for another strafing run…and another, and another, and a fourth. Bennett’s guns had the desired effect, giving the South Vietnamese marines and their U.S. marine advisor a chance to pull away to safety.

Ignoring the advice not to repeatedly fly over larger NVA units, Bennett and Brown lined their Bronco up for one more strafing pass – their fifth. Using the final rounds from their guns, the Bronco unleased more devastation on the NVA forces below. As the departing Bronco zoomed upwards and to the left, a SA-7 Strela missile quickly ascended toward the plane, attracted by the heat from the two engines. The 2.5-pound warhead exploded near the Bronco’s left engine, destroying the turboprop and sending hot shrapnel into the nearby canopy and fuselage. With one engine destroyed and one main mount landing gear now hanging down below the plane, Bennett and Brown’s wounded aircraft was in serious trouble. Flames and smoke could be seen coming from the stricken plane as it struggled to stay in the air at around 600 feet.

Sacrifice: Life and Death Over the Tonkin Gulf

Still mindful of doing all he could to prevent harm to the South Vietnamese forces on the ground nearby, Bennett chose not to immediately dump his remaining phosphorous rockets and fuel above their heads. Instead, Bennett radioed a Mayday distress call over the radio and headed out over the nearby waters of the Gulf of Tonkin, where he did finally jettison his stores.

As a well-trained Air Force pilot, Bennett no doubt ran through a checklist of options. Could his Bronco make an emergency landing on a nearby airfield? While this was briefly considered, the growing flames reported by Bennett’s wingman meant that it was more likely the Bronco would explode before reaching an airfield.

Next on the checklist was ejection. The OV-10 Bronco was equipped with LW-3B ejection seats, allowing the pilot and backseater to eject free from a damaged aircraft. As Covey 87 and Wolfman 45 considered ejecting, Brown turned his head and noticed that the SA-7 had shredded the parachute attached to his ejection seat. For Brown, there would be no possibility of ejecting. And while Bennett retained the ability to eject, the pilot would never forsake his backseater to a certain death.

Time was of the essence. The burning Bronco could explode at any moment.

No to diverting to a nearby airfield. No to ejection. The choices then were narrowed down to just one more – a choice that came with one truly grave consideration. The only viable option left was to crash-land the Bronco in the waters of the Gulf of Tonkin.

As mentioned earlier, one of the strengths of the OV-10 Bronco as an observation plane was its large bubble canopy. Being seated within this bulbous plexiglass enclosure gave the pilot and the observer excellent visibility, but the large canopy was also not structurally strong. It was common knowledge throughout OV-10 units that the pilot was unlikely to survive a ditching in the ocean. In all previous situations, the front cockpit had collapsed upon impact.

To ditch in the waters below would give Brown a good chance at surviving but would also assign Bennett very long odds of the same. As Brown would state later, [Captain Bennett’s] disregard for his own life surely saved mine when he elected not to eject.”

With the re-emergence of flames, Bennett led his Bronco to the waters below. As they flew a mile off the Vietnam coast, they struck the water. The main mount landing gear hanging from the plane caused the Bronco to spin to the left, flipping the plane over onto its back. With both pilots now submerged, the struggle for survival became supreme. Brown fought to get out of his seat harness and managed to escape the plane and rise to the surface. After taking a few gulps of air, Brown dove back under the water to help Bennett, but his efforts were unsuccessful – Bennett was dead.

Captain Brown was recovered by a U.S. Navy helicopter and taken to the nearby USS Tripoli (LPH-10) for medical treatment. Bennett’s body was recovered from the plane the next day.

Courage: “The Bravest Man I’ve Ever Met”

Steven Bennett’s death was one of the more than 50,000 that American forces suffered during the Vietnam War. In Bennett’s case a combination of his piloting skill, commitment to serve his comrades, and his sacrifice – the ultimate sacrifice – ensured Captain Brown’s survival. In addition, Bennett’s repeated low-level strafing attacks allowed the threatened South Vietnamese marines and their US Marine advisor to escape almost certain destruction. Michael Brown would later describe Bennett as the “bravest man I’ve ever met.”

In a larger sense, the brave and resolute actions of aviators such as Captain Steven Bennett played a critical role in defeating the NVA’s Easter Offensive. North Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap’s offensive would cost the NVA more than 100,000 troops captured or killed, and the city of Quang Tri would be recaptured by the South Vietnamese in September of 1972.

The Medal of Honor

Bennett’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Gabriel Kardong, recommended his aviator for the Medal of Honor, writing that “Captain Bennett made the decision to ditch and thereby made the ultimate sacrifice.”

On August 8, 1974, Steven Bennett’s wife, Linda and his two-and-a-half-year-old daughter Angela were on hand at the Blair House in Washington DC to receive Captain Bennett’s posthumous Medal of Honor from Vice President Gerald Ford. Ford was tapped to make this presentation since President Richard Nixon, overwhelmed by the Watergate scandal, announced his resignation on the same day at the White House.

Captain Bennett’s Medal of Honor citation said it best.

Although Capt. Bennett had a good parachute; he knew that if he ejected, the observer would have no chance of survival. With complete disregard for his own life, Capt. Bennett elected to ditch the aircraft into the Gulf of Tonkin, even though he realized that a pilot of this type aircraft had never survived a ditching. ….Capt. Bennett’s unparalleled concern for his companion, extraordinary heroism and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty, at the cost of his life, were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself and the U.S. Air Force.

Excerpt from Captain Steven Bennett’s Medal of Honor Citation

It has been more than 50 years since Steven Bennett’s last flight over Vietnam, but his example remains as strong today as it did that fateful day in Vietnam. A determination to serve in harm’s way, even when that was unpopular. A commitment to do all he could to help his comrades on the ground, even when that demanded actions that created great risk. And his selfless sacrifice so that his crewmate could live, even at the risk of his own life, are powerful reminders of the best that serve in our military and deserve our nation’s highest military decoration.

Video

Sources:

- Captain Steven Bennett’s Medal of Honor Citation

- “Impossible Odds in SAM-7 Alley”, Air Force Magazine, Dec. 2004

- “Valor: A Gift of Life”: Air Force Magazine, Aug. 1998

- Bennett – Capt. Steven L Bennett, Air Force Historical Support Division

- County honors ‘greatest hero’ with historical marker – Palestine Herald-Press

- OV-10 Bronco Was the Right Weapon for Vietnam – Defense Media Network

- The 20th Tactical Air Support Squadron – FAC Association