Normandy Campaign – Battle of the Falaise Pocket

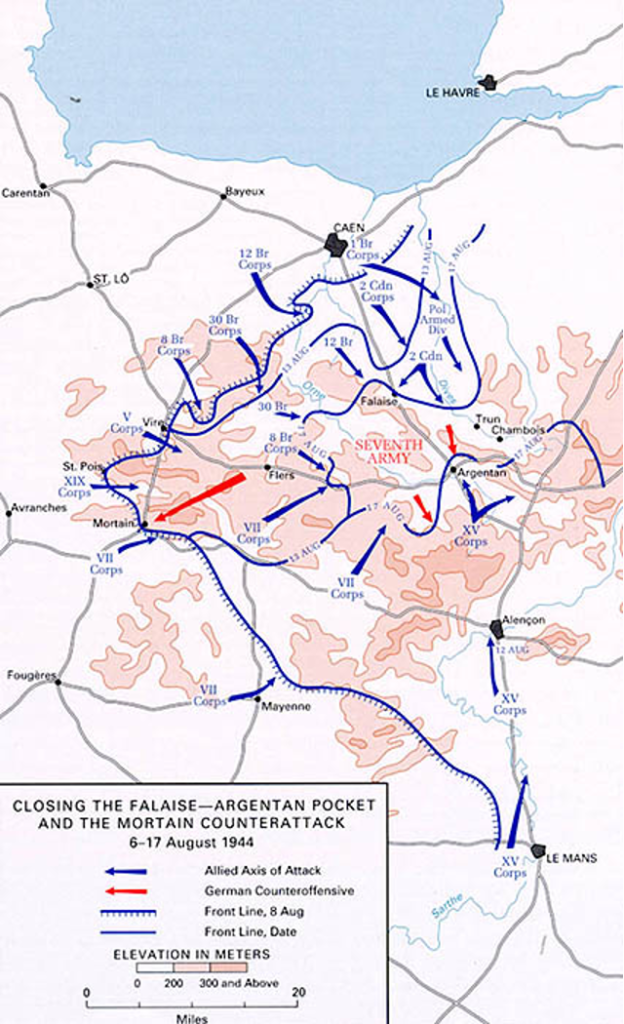

Hitler’s obstinacy in his defense of Normandy created a clear opportunity for the Allies. The Germans had launched a counterattack with that forces could be mobilized by August 7. By the end of the day it was clear the offensive, which had caught the Allies by surprise, was not going to succeed in its mission of cutting off the Third Army and restoring the German front. Field Marshal Günther von Kluge, the German commander in charge of the offensive, was ordered to press the attack by Hitler. First Canadian Army had started an offensive toward Falaise, and in early August 1944 there was a possibility that Patton’s Third Army could link up with the Canadians and trap the German Army Group that had launched the offensive.

On 11 August, Hitler had a withdrawal from the Mortain in order to safeguard the German 7th Army’s rear. However, even this was only temporary as Hitler was resolved to counterattack and attempt to break the Allied advance through Normandy. The troops in the pocket, however, were unable to mount a major, coordinated blow in any direction. German forces were low on fuel and ammunition and under constant pressure from Allied air and ground forces. At one point during battle the Kluge, was stranded for a day after Allied planes strafed his command car. On August 16, Kluge recommended immediate withdrawal from the Falaise Pocket.

Hitler agreed with the retreat but replaced Kluge. German forces were under constant attack from Allied air power and artillery. Some German units panicked or mutinied, but others continued to grimly fight on to maintain a small outlet for escape. Observing the area after the battle, an American officer saw “a picture of destruction so great that it cannot be described. It was as if an avenging angel had swept the area bent on destroying all things…” By August 21 the Falaise Pocket had been completely surrounded by Allied forces, trapping some 50,000 Germans within and ending effective German resistance in Normandy.

John Hawk: Fighting Off Tigers

It was not until August 19 that the 90th Division’s 359th Infantry Regiment got its orders to move on Chambois. Chambois was located directly to the rear of the German Seventh Army. By August 20th the 359th had been pounded by German attacks attempting to break out of the Allied encirclement of the Falaise Pocket.

John Hawk, who had enlisted after graduating high school and who had only landed in Normandy a few weeks earlier, was fighting with the 359th to keep the Germans from escaping. On August 20 Hawk and the machine gun squad he was commanding were dug in near an orchard when the enemy counterattacked with a pair of Tiger tanks and infantry. The Germans knocked out several American machine guns, including Hawk’s.

Hawk took up a position behind an apple tree and began to direct fire for American tank destroyers. American tank destroyers were able to blunt the German attempt to escape. At one point a German tank shot at Hawk, destroying the tree he was using as cover and wounding in his leg. Hawk retreated from his now-exposed position and while retreating physically ran into a German tank. Shooting at the tank commander with his rifle bought him a few moments to escape back to friendly tank destroyers. Despite his leg wound Hawk continued directing fire until the remaining 500 Germans assaulting the orchard surrendered.

Hawk’s heroics did not end when he returned home from World War. A longtime teacher and principal in Bremerton, Washington, he became a familiar face who had tremendous impact on schoolchildren in his community.

Hawk’s Medal of Honor ceremony was notable in that, because he was tired of travelling across the country, President Harry Truman came to Hawk. Instead of in Washington D.C., which President Theodore Roosevelt had made the usual place of giving a Medal of Honor, Hawk received his Medal of Honor from Truman in Olympia, Washington on June 24, 1945.

Medal of Honor Citation

He manned a light machinegun on 20 August 1944, near Chambois, France, a key point in the encirclement which created the Falaise Pocket. During an enemy counterattack, his position was menaced by a strong force of tanks and infantry. His fire forced the infantry to withdraw, but an artillery shell knocked out his gun and wounded him in the right thigh. Securing a bazooka, he and another man stalked the tanks and forced them to retire to a wooded section. In the lull which followed, Sgt. Hawk reorganized 2 machinegun squads and, in the face of intense enemy fire, directed the assembly of 1 workable weapon from 2 damaged guns. When another enemy assault developed, he was forced to pull back from the pressure of spearheading armor. Two of our tank destroyers were brought up. Their shots were ineffective because of the terrain until Sgt. Hawk, despite his wound, boldly climbed to an exposed position on a knoll where, unmoved by fusillades from the enemy, he became a human aiming stake for the destroyers. Realizing that his shouted fire directions could not be heard above the noise of battle, he ran back to the destroyers through a concentration of bullets and shrapnel to correct the range. He returned to his exposed position, repeating this performance until 2 of the tanks were knocked out and a third driven off. Still at great risk, he continued to direct the destroyers’ fire into the Germans’ wooded position until the enemy came out and surrendered. Sgt. Hawk’s fearless initiative and heroic conduct, even while suffering from a painful wound, was in large measure responsible for crushing 2 desperate attempts of the enemy to escape from the Falaise Pocket and for taking more than 500 prisoners.