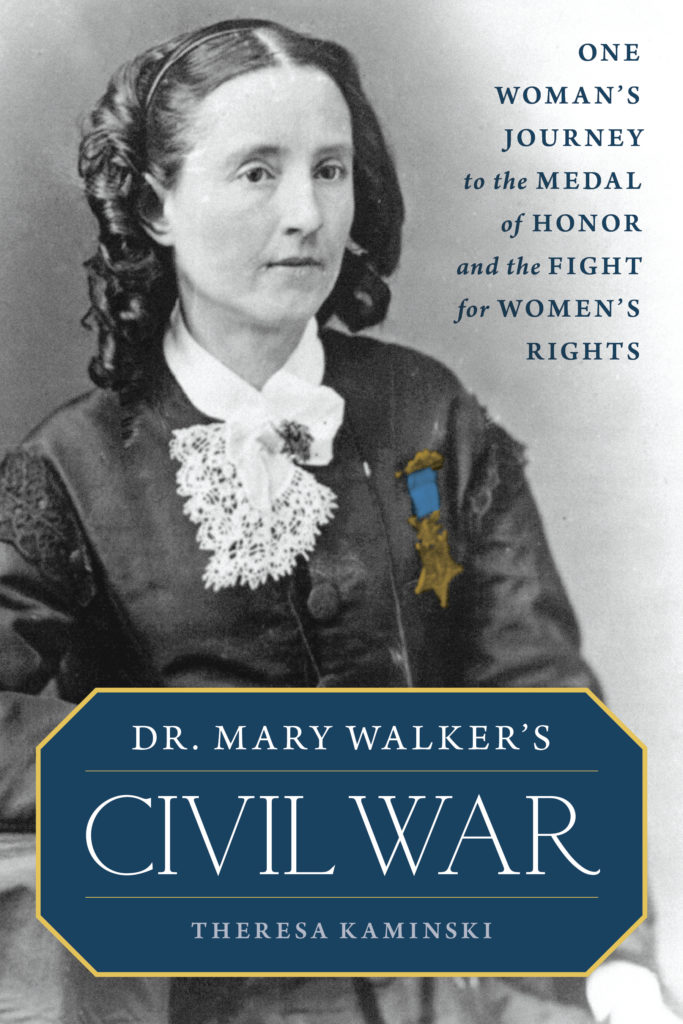

Dr. Mary Walker remains the only female recipient of the Medal of Honor. Walker was determined to serve her country during the American Civil War. Seeking to overcome restrictions on females, Walker was a tireless advocate for an increased role for women in the U.S. Army and in society. The National Medal of Honor Museum had the opportunity to speak with author Theresa Kaminski about her new book, Dr. Mary Walker’s Civil War – a new biography of this most remarkable person.

What in Mary Walker’s upbringing helped to shape her character and focus on women’s rights?

Mary Walker’s parents, Alvah and Vesta, get a lot of credit for this. Originally from Massachusetts (some of Alvah’s ancestors had come over on the Mayflower), the young couple moved to central New York in the 1820s. They settled first in Syracuse, then in Oswego Town, where Mary was born in 1832. The Walkers were progressives and freethinkers who encouraged their children to approach religion intellectually and to embrace reform. They supported abolition, temperance, and gender equality. Mary absorbed these ideas and took them to heart. They became the core of who she was.

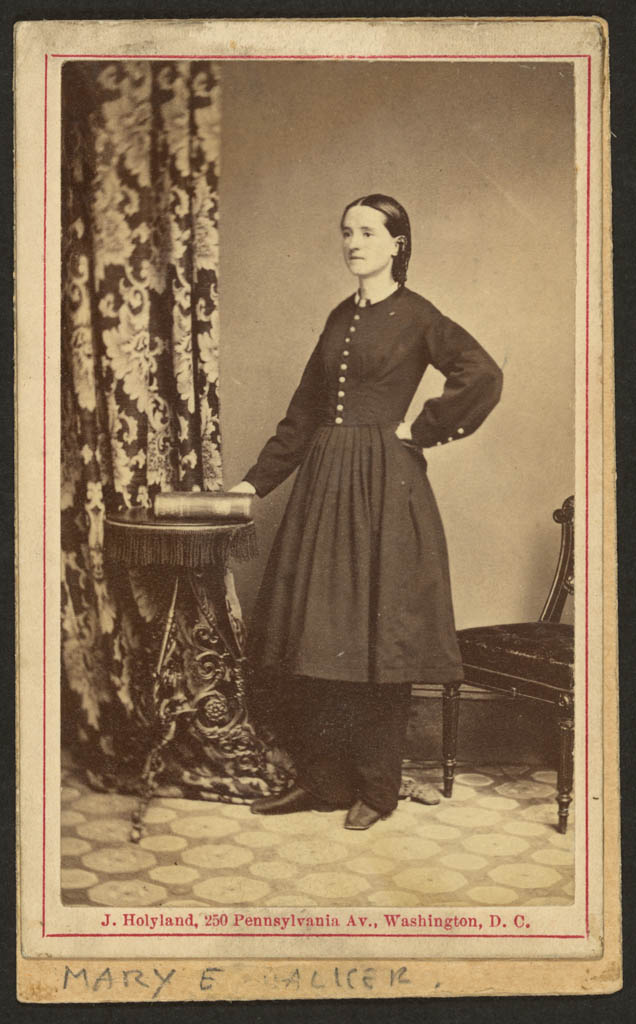

These beliefs led Mary Walker to adopt what was known as the Bloomer costume: trousers worn under a knee-length skirt. She wore a version of this outfit for the rest of her life.

It also helped that she lived in a place where most of the inhabitants shared this reforming spirit. Abolitionist speakers, including Sarah and Angelina Grimké, Maria Stewart, and Fanny Wright who also raised issues of women’s rights, traveled through central and western New York in the 1830s. Wealthy philanthropist and reformer Gerrit Smith was a frequent visitor to Oswego.

Tell us more about Mary Walker’s medical training and professional interests.

Alvah and Vesta Walker believed in equal education for boys and girls, and they made sure their daughters and son received at least the basics. The Walker siblings all learned first from their parents, who established a free school for the local children on their Oswego property. Mary was intrigued by her father’s collection of medical books, most of which espoused an eclectic approach that emphasized diet, exercise, physical therapy, and natural remedies. She decided to become a doctor.

After learning everything her parents could teach, Mary enrolled at the Falley Seminary, a nearby co-educational school that prepared her for teaching. She worked for about two years at this profession so she could save money for medical school. In 1853, Mary entered the Syracuse Medical College, one of the few medical schools that accepted female students and one that emphasized the eclectic approach. She graduated with honors in 1855.

Mary married Albert Miller, also a doctor, later that year. They set up medical practices in Rome, New York. Mary primarily treated women and children, and she became very interested in maternal health issues. For the rest of her professional career, she remained attentive to these concerns.

The beginning of the 1860s was a difficult time for Mary Walker. As her marriage disintegrated, so did the political union holding the United States together. Mary took action on both counts. She divorced Albert Miller, and in 1861 she traveled to Washington, D.C. to work for the war effort.

Mary Walker was obviously a very patriotic person and a trained medical doctor. Why were her requests to enter the Army denied and resisted?

Because she was a woman. Medicine was viewed as a man’s profession; military service was for men. The Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, saw no reason for making an exception in Mary Walker’s case. She asked him directly for a military commission so she could serve in the army as a medical doctor. He refused. Surgeon general Clement Finley also turned down Dr. Walker. And all this despite the fact that the army desperately needed trained medical personnel.

The army was willing to hire women to work as nurses, and it appointed hospital reformer Dorothea Dix to coordinate those efforts. Dix didn’t focus on medical training for these women, however. She only sought to recruit respectable white, middle-class women who would take directions from doctors and not challenge their authority.

There were instances of women disguising themselves as men to join the army. We’ll never know how many did so because most likely went undetected. But Mary Walker never had any intention of hiding who she was. She wanted recognition as a doctor.

Despite all the resistance, how did Dr. Walker serve the Union during the Civil War?

For most of the war, she worked as a volunteer doctor, receiving no pay for her services. She started at the Indiana Hospital in Washington. Its surgeon in charge didn’t care that she was a woman and welcomed her help.

By late 1862, Dr. Walker started going where the army went. She was with General Burnside’s men in the aftermath of the Battle of Fredericksburg. In 1863, she traveled with the Army of the Potomac. She treated soldiers after the Battle at Gettysburg. By the fall, Dr. Walker moved on to Chattanooga, where her hospital work attracted the attention of General George Thomas, head of the Army of the Cumberland.

In early 1864, Thomas decided to hire Dr. Walker as a civilian contract surgeon for the 52nd Ohio, which was encamped in northern Georgia.

Is it true that Mary Walker engaged in espionage for the Union during the Civil War?

Yes, in her capacity as a contract surgeon, she gathered intelligence about Confederates whenever she traveled outside the camp to treat local civilians. Dr. Walker did this despite the risk to her personal safety. The area still wasn’t secure. Confederate troops and sympathizers were all over, and many of them were suspicious of Dr. Walker. In April 1864, she was detained by enemy soldiers and spent a few months at Castle Thunder Prison in Richmond.

As the only female recipient, tell us about the circumstances leading to her receiving the Medal of Honor in 1865.

Dr. Walker never gave up trying to secure a military commission. Even after the war ended in April 1865, she asked for a retroactive one. By this time, she had gained a lot of support from politicians and officers who admired her medical work and her bravery in intelligence gathering. Plus, she’d spent time as a prisoner of the Confederacy. The idea began to spread that she should receive some public recognition.

Discussions went on at very high levels: President Andrew Johnson, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt all tried to figure out how Dr. Walker should be honored. When Holt concluded a commission wasn’t possible, he suggested the Medal of Honor. Johnson concurred and issued the award in November 1865.

Dr. Mary Edward Walker: Medal of Honor Citation

What did the Medal of Honor mean to Mary Walker?

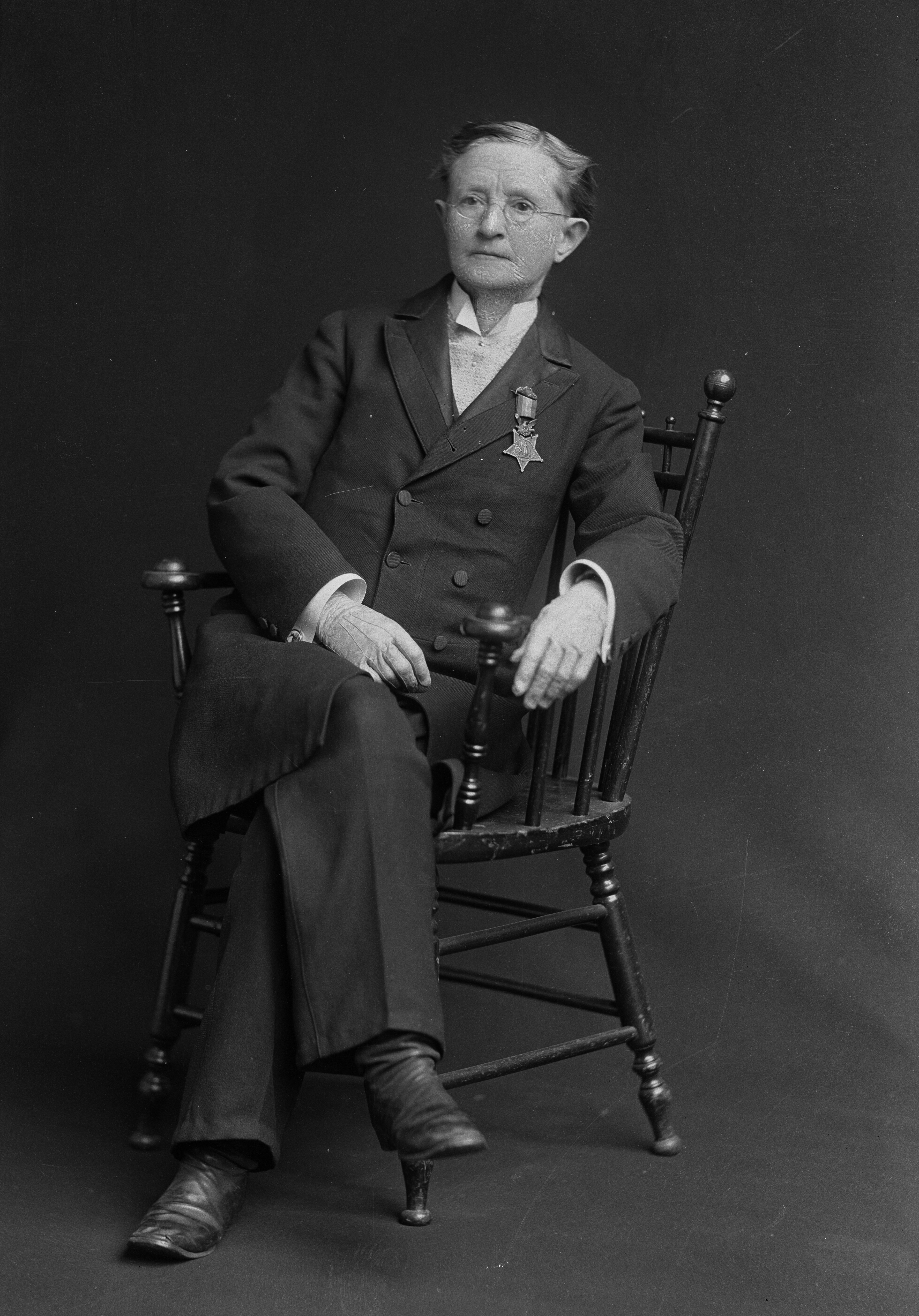

It meant everything. For her, the medal validated all the work she did during the war and recognized her contributions as a woman doctor. It provided the connection to the army she longed for. I think she hoped other women would soon be able to join the military, and that more of them would someday receive the medal, too.

The Medal of Honor also helped secure Dr. Walker’s reputation as a women’s rights advocate. She spent the rest of her life arguing for equal opportunity in education and employment for women. And she campaigned for women’s suffrage.

As you reflect upon Mary Walker, what impresses you the most? What should we remember from her remarkable life?

Her self-confidence. Dr. Walker thought well of her intellect and her capabilities. She knew who she was and how to stay true to herself. Yet she wasn’t self-absorbed or selfish. Dr. Walker chose to practice medicine, she chose to support the Civil War, she chose to get involved with the suffrage movement–all so she could help others. It was pretty astonishing for a woman born and raised in the 19th century to live out her declaration: “I will always be somebody.”

The Book: Order “Dr. Mary Walker’s Civil War” on Amazon

Author: Dr. Theresa Kaminski

Theresa Kaminski earned her Ph.D. in history, with a specialization in American women’s history, from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. As a professor of history at a state university in Wisconsin, she taught a variety of courses in American history and American women’s history. She has also published three books on American women in the Philippines during World War II, most recently, Angels of the Underground. Theresa is currently completing a biography of singer, actor, writer, and cowgirl extraordinaire, Dale Evans. Please visit her website at theresakaminski.com and/or follow her on Facebook at TheresaKaminskiHistorian and on Twitter @KaminskiTheresa.