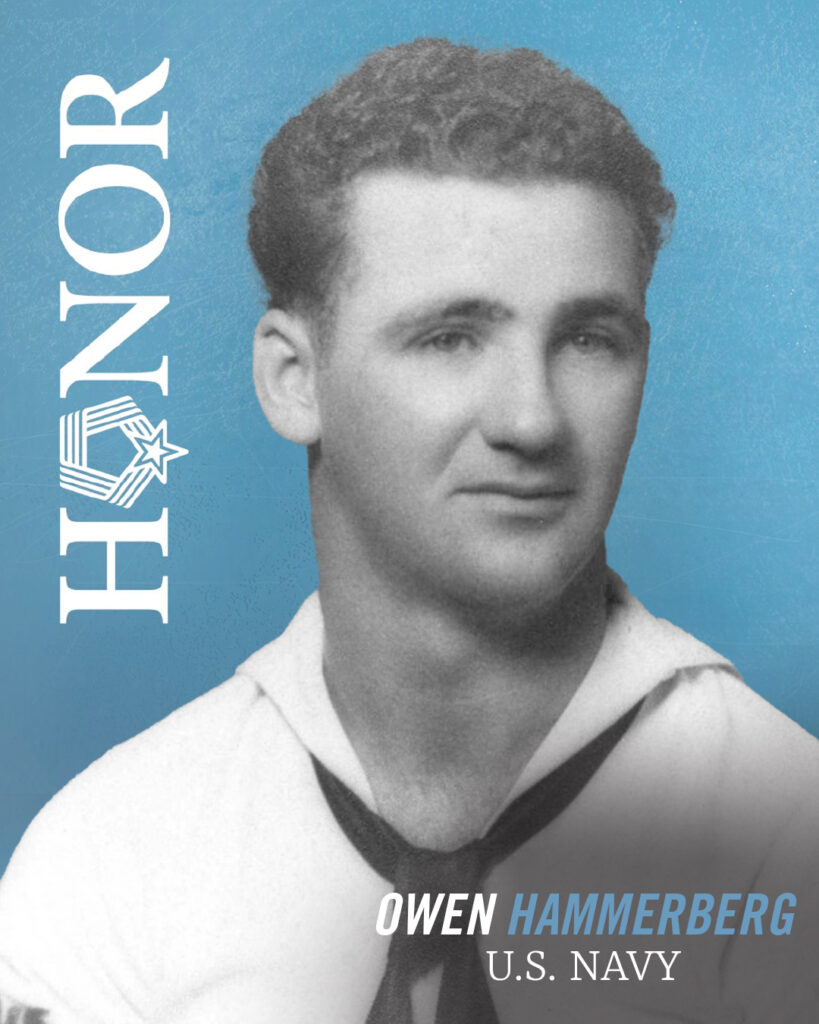

Meet Navy MOH Recipient Owen Hammerberg

Growing up, Owen Hammerberg moved frequently with his family. They finally settled in Flint, Michigan, when he was a teenager. After dropping out of high school, he hitchhiked west and found work as a ranch hand. By 1941, he had joined the Navy. He was young — only 21 — and full of ambition.

Following basic training, Hammerberg received assignments to USS Idaho (BB-42) and USS Advent (AM-83). Aboard USS Advent, he gained notoriety for his heroic efforts to free a cable tangled in a mine below water, preventing an explosion. This newsworthy action received notice from peers and officers, and Hammerberg enrolled in Navy dive school. He excelled, completed training, and transferred to the Pacific Fleet Salvage Force, Mobile Diving Unit 1 in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

On May 21, 1944, several ships full of ammunition and fuel were stationed in the West Loch at Pearl Harbor. Following the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, West Loch remained immune from damage and was the best place to moor ships as they prepared for upcoming missions. However, under mysterious circumstances, one ship blew up, causing a domino effect. Other ships caught fire, forcing the Navy to sink them in an effort to prevent further damage and loss of resources, men, and weaponry. By 1945, the Navy felt it was safe to extract the sunk ships and clean up the West Loch. Special diving teams were called to support the mission, including Hammerberg’s.

A Race Against Time

Hammerberg’s team removed their assigned ship and cleared the water without issue. But another nearby team had less prosperous results. Two of their divers were trapped in steel and cables trying to remove their ship, which was below the surface in 40 feet of water and 20 feet of mud.

On February 17, 1945, Boatswain’s Mate Second Class Hammerberg volunteered to find George Fuller and Earl Brown, the two trapped divers. It was a risky mission — the ship’s hull could cave in at any time, and the possibility of sharp debris tearing Hammerberg’s lifeline was high. Unable to see through the thick mud, Hammerberg carefully pushed through the dark water, groping and reaching for something to direct his rescue efforts. After five strenuous hours, he found Fuller first. Fuller shook his hand underwater before bobbing up to the surface.

Despite exhaustion setting in, Hammerberg continued to search for Brown. He combed the wreckage, slowly ruling out sections. About 18 hours later, he located Brown, just as a cave-in took place. A large, dense piece of steel pinned Hammerberg on top of Brown, crushing him instantly. Brown survived, due to Hammerberg’s incredibly brave, selfless act. After two days, a second dive team, a Filipino man and his son, found Brown and recovered Hammerberg’s body. A year later, Hammerberg’s parents, Jonas Hammerberg and Elizabeth Moss, accepted the Medal of Honor on their son’s behalf at Grosse Ile Naval Air Station in Grosse, Michigan.

A Legacy of Selfless Sacrifice

Hammerberg’s heroic efforts did not go unnoticed, nor were they forgotten. For 100 years, the Army and Navy had bestowed Medals of Honor based on varying guidelines for each branch of service. In 1963, Congress created a singular, unifying set of standards that clearly dictated actions that qualified a Recipient for a Medal — regardless of military branch. Hammerberg was the final Recipient to earn the Medal posthumously for a non-combat action, prior to the implementation of the new rules.

Hammerberg remains the only Navy Diver to earn the Medal during World War II, along with several other medals for his heroic sacrifice and selfless acts of courage and bravery. In 1954, USS Hammerberg (DE-1015), a destroyer escort, was commissioned in his honor. Other reminders of his valiant acts of service can be seen throughout Michigan: Hammerberg Road in Flint, a park in Detroit, and a monument by the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 5966 in Menominee. But perhaps the most honorary and noteworthy recognition is Hammerberg’s Medal and naval uniform, which are on display at the Michigan Heroes Museum in Frankenmuth.

Today, Hammerberg remains an inspiration and a shining example of what it means to put service before self. His legacy continues to encourage Naval personnel and Michigan residents to help one another however they can.