Date of Action: October 1942-January 1943

Squadron: Marine Fighting Squadron 121 (VMF-121)

Location: Over and Near Guadalcanal Island

Joe Foss was a United States Marine Corps pilot and one of the leading American aces of World War II. Assigned to Marine Fighter Squadron 121 (VMF-121) in 1942 as executive officer, Foss was sent with his squadron to Henderson Field on Guadalcanal Island in the South Pacific. Arriving at a time when the air campaign over Guadalcanal was at its most intense, Foss and his airmen quickly found themselves in near-daily battles with the Japanese. In three months of intensive combat starting in October 1942, Foss was credited with shooting down 26 Japanese aircraft—tying him with the all-time American record set by Eddie Rickenbacker in World War I. Foss, the cigar-chomping fighter ace with movie star good looks, quickly became a household name in the United States. Suffering from a bad case of malaria, Foss returned to the United States in March of 1943 and received the Medal of Honor from President Franklin D. Roosevelt that May. After World War II, Foss continued to serve his nation in the South Dakota Air National Guard and eventually rose to the rank of Brigadier General. In 1954 he was elected to the first of two terms as governor of South Dakota, and in 1959 he became the first commissioner of the American Football League. A lifelong hunter and outdoorsman, Foss starred in ABC’s The American Sportsman series and later was president of the National Rifle Association.

From South Dakota Farmhouse to the Skies Above Guadalcanal

On April 17, 1915, Joseph J. Foss was born to a Norwegian-Scots farming family outside Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Growing up on a Depression-era farm, Foss learned to become an accomplished hunter at an early age. In 1927, an 11-year-old Foss saw Charles Lindbergh when the famed aviator visited Sioux Falls. Riding home afterwards, he reportedly told his father, “I’m going to be bigger than Lindbergh someday.” Four years later, after his father purchased him a flight in a Ford Tri-Motor airplane, Foss became smitten with the idea of becoming an aviator. Sensing that America would eventually be drawn into World War II, he scraped together enough money to hitch-hike 300 miles to Minneapolis, Minnesota, where he enrolled in the naval aviation cadet program. Foss excelled in the highly competitive program and later earned his wings at NAS Pensacola in March of 1941. He was commissioned a lieutenant in the Marine Corps.

It’s remarkable to think that this future ace was almost prevented from flying in combat at all. At 26 years of age, Foss was considered too old for combat, and many of his superiors preferred keeping him in the States as an instructor. He pined for a chance to prove himself as a fighter pilot, however, and repeatedly pleaded with his leaders for a front-line assignment. Foss managed to wrangle a position with a reconnaissance squadron based in San Diego but remained out of the fight until New Year’s Day 1942, when he learned that he was to become the executive officer of Marine Fighter Squadron 121 (VMF-121). Flying the Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter, Foss and his squadron were deployed to Guadalcanal Island as part of Operation Watchtower in early October 1942. It was here that Joe Foss would finally be given his chance to prove his fighting mettle.

Foss’s Flying Circus

Catapulted off the deck of the escort aircraft carrier USS Copahee on October 9, 1942, Foss and the other members of VMF-121 flew their Wildcats to Guadalcanal and their new home at Henderson Field. Becoming part of the fabled Cactus Air Force, Foss and his men were welcome reinforcements for an air group worn out by constant attacks and rampant diseases. The rough airfield, hewn from the jungle, was regularly bombed by Japanese aircraft and blasted by battleships and cruisers. Struggling to hold onto the island, the Cactus Air Force was tasked with defending their base and striking the Japanese ships seeking to resupply their army on the island.

Shortly after arriving, Foss sought out the leading Marine fighter pilots that had been on the island since August. From flying legends like Captain Marion Carl and future Medal of Honor recipient Major John Smith, Foss gleaned tips that would help him and his men to survive in the skies above.

On October 13, 1942, just four days after arriving, Foss engaged in his first dogfight and shot down his first plane—a Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter. With his “hair standing on end and his mouth dry as cotton” Foss was, in turn, jumped by three other Zeros, and the veteran Japanese pounded his plane with machine gun and 20mm cannon fire. With dark smoke pouring out of his stricken engine and tracer bullets flying past his canopy, Foss managed to glide his fighter back to Henderson Field. As he would later state about this first day’s combat, “I learned two important lessons that day . . . I had to stay alert to stay alive, and no one ever caught me asleep at the switch again or so intent on an attack that I failed to keep looking around.”

Foss and his squadron mates quickly learned what it took to stay alive above Guadalcanal. A natural shot, he learned to take advantage of the Wildcat’s robust construction and heavy firepower. He and his squadron also came to rely upon the Thach-Flatley Weave: a multi-plane fighter tactic that made the Wildcat less vulnerable to the more maneuverable Japanese fighters.

During almost daily action over the South Pacific, Foss’s score rose quickly and dramatically. On October 18, he led his fighters in an attack and shot down three Zeroes in quick succession. On October 25, Foss shot down five different Japanese planes in two missions—the Marine Corps’ first “ace in a day.” During his first twelve days in theater, he had scored sixteen confirmed victories.

“If you blink, you could miss the fight. If you blink during the fight, you could die. That, in fact, is the trick to aerial combat. There is virtually no time to think about acting or reacting. The impulse and the act must be one.”

Joe Foss

Despite Foss’s growing aerial prowess, danger always lurked in the skies. His Wildcat fighters frequently returned with bullet holes in the wings and fuselage. On November 7, Foss’s fighter was struck by bullets from a rearward firing machine gun aboard a Japanese scout plane. The engine on Foss’s Wildcat sputtered, and he was forced to crash land in the contested waters of Ironbottom Sound. Escaping from his cockpit as the sea poured in, Foss drifted in his Mae West life preserver, hoping that the Japanese or sharks would not get him. Growing weak as he drifted for hours during a rainstorm, Foss was rescued by an Australian coast watcher and natives from the nearby Malaita island.

Returning to his squadron on Guadalcanal, Foss and his “Flying Circus” continued to engage wave after wave of Japanese aircraft flying down “the Slot” to Guadalcanal. On November 13, Foss and his men attacked Japanese ships, including the massive battleship Hiei taking part in the epic Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Diving almost vertically against the huge capital ship, he described “bouncing .50 calibers off the decks of the battleship as pom-pom guns pumped away at me.” Foss would later describe the two strikes against the Hiei as the most dangerous he ever flew. Pounded from the air and sea, the Hiei, when it foundered near Savo Island on November 14, became the first Japanese battleship sunk in the war.

On January 15, 1943, Joe Foss shot down a Zero for his 26th confirmed victory, becoming the leading American ace of war and matching the all-time victory record set by Eddie Rickenbacker in World War I. Ten days later, on January 25, Foss led a group of eight Wildcats and four P-38 Lightnings against a large formation of Japanese fighters and dive-bombers headed for Guadalcanal. Foss and the others resisted getting tangled with the Zero fighter escort and instead tore into the Japanese dive bombers. Showing remarkable tactical discipline, Foss’s outnumbered fighters disrupted this large raid and prevented the Japanese from bombing the airfield.

Despite all his successes in the skies, Foss was losing a more insidious battle on the ground. Like most who stayed on the pestilential island, he had contracted a severe case of malaria. Having lost 37 pounds since his arrival, Foss suffered from frayed nerves and weakened body that made flying ever more difficult.

With 26 kills, Foss had become a national hero, and Generals Francis Mulcahy and Roy Geiger sensed it was now time to send their ace back to the States. What the pilot didn’t know was that Geiger had also submitted a recommendation that Captain Joe Foss receive the Medal of Honor for “repeated acts of heroism and intrepidity at the risk of his life far beyond the call of duty and without detriment to his mission.”

Far more than just a top fighter ace, Captain Foss proved to be an accomplished tactician and a superior squadron leader. As reported in an April 1943 edition of The Saturday Evening Post, “it was only his shrewd leadership and knowledge of combat tactics that saved the Americans and their precious airfield from a hail of destruction.”

Receiving the Medal of Honor

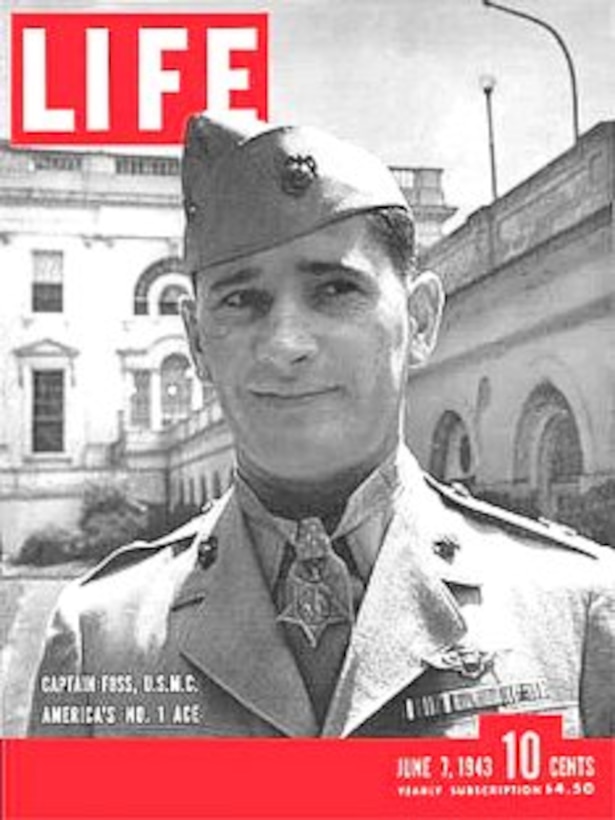

Returning to a hero’s welcome in the States, Captain Foss was sent on a nationwide publicity and speaking tour. On May 18, 1943, accompanied by his wife and mother, he received the Medal of Honor from President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House. Roosevelt, seated behind his Oval Office desk, turned to Foss and read his citation with the newsreel cameras rolling. Foss then leaned forward so that the president could place the medal around his neck. Wearing his new medal, he was photographed by Life Magazine, and his image was featured on the cover of the June 7, 1943 edition, which chronicled, “an exciting experience for this country boy.”

In February of 1944, Foss returned to the Pacific Theater to lead Marine Fighter Squadron 115 (VMF-115) which flew the new F4U Corsair fighter. Flying from an airfield on Emirau Island, he did not add to his score, but was able to meet luminaries such as his boyhood idol, Charles Lindbergh. Eight months into this second tour, Foss began to suffer once more from malaria and returned to the States to receive treatment.

Post-War Experiences

Joe Foss’s national fame served him well as he transitioned from active duty after World War II. He first established a charter aviation and flight instruction company—Joe Foss Flying Service—in Sioux Falls.

Wanting to maintain his military flying status, Foss joined South Dakota’s 175th Air National Guard as an Air Force lieutenant colonel. Called to active duty as a colonel, he hoped to fly combat missions at the start of the Korean War, but he was instead assigned to the Central Air Defense Command as Director of Operations.

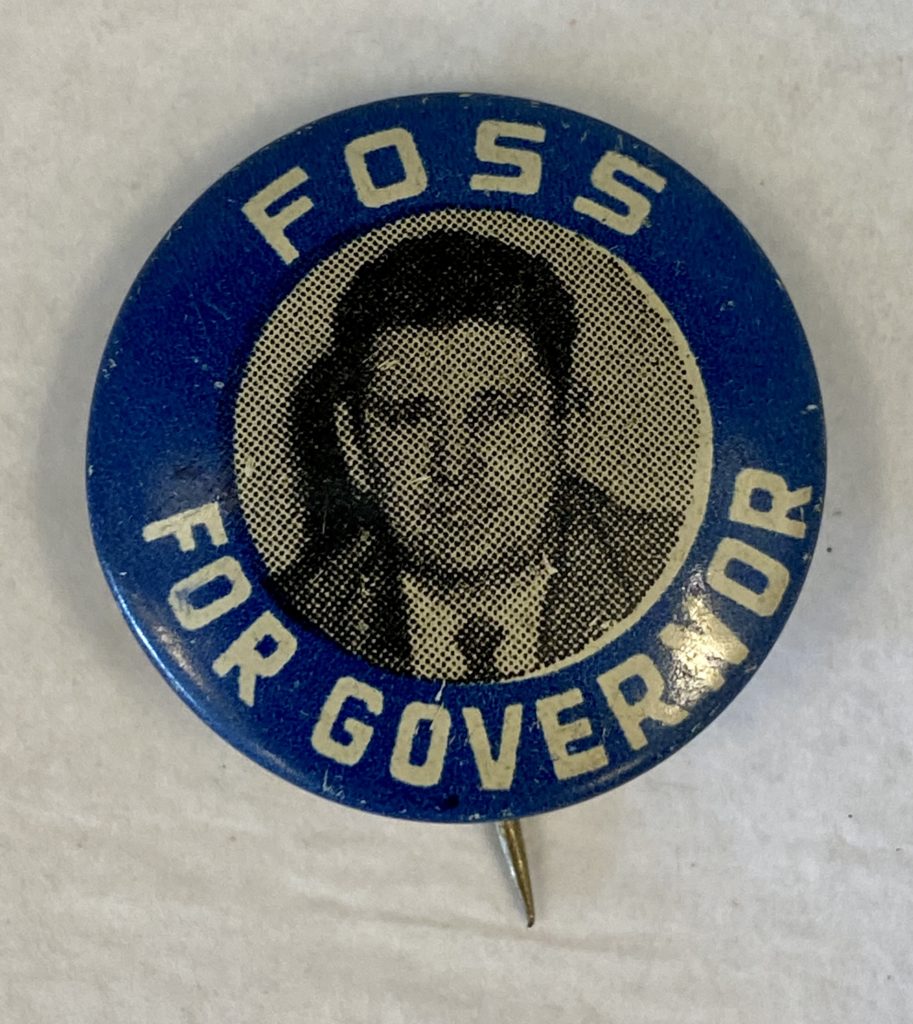

In 1948 Foss entered the world of politics. Using one of his planes during the campaign, he was elected as a Republican representative to the South Dakota legislature. And in 1955, Foss took office as South Dakota’s youngest governor. During his two terms, he sought to recruit new industries to the state, promote a friendlier business climate, and control government spending.

In 1959, Foss became the first commissioner of the new American Football League. Despite having little experience in professional sports, he was adept at managing the owners’ complex egos, maintaining discipline with the players, and signing lucrative television broadcasts that buoyed the league’s prospects. Long a proponent of merging the AFL with the more established NFL, Foss stepped aside from his commissioner role just months before the terms of a merger were settled in June of 1966.

Having been a lifelong hunter and outdoorsman, Joe Foss was asked to host the nationally syndicated show The American Sportsman shown on ABC television. This series featured Foss and his friends hunting or fishing in locations across the globe.

A gun owner and second amendment advocate, Foss served two terms as president of the National Rifle Association. He was a tireless spokesman for gun rights and was featured holding a revolver on the cover of the January 29, 1990 issue of Time Magazine.

Foss was active in supporting charities such as the National Society of Crippled Children and Adults, the Easter Seals, and Campus Crusade for Christ. He died in Scottsdale, Arizona, on New Year’s Day, 2003, from complications resulting from a recent stroke.

“I told him that [the Medal of Honor] had opened many doors to me….Once inside, it was up to me to prove myself.”

Joe Foss to a reporter

Medal of Honor Citation

For outstanding heroism and courage above and beyond the call of duty as Executive Officer of a Marine Fighting Squadron, at Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. Engaging in almost daily combat with the enemy from October 9 to November 19, 1942, Captain Foss personally shot down 23 Japanese aircraft and damaged others so severely that their destruction was extremely probable. In addition, during this period, he successfully led a large number of escort missions, skillfully covering reconnaissance, bombing and photographic planes as well as surface craft. On January 15, 1943, he added three more enemy aircraft to his already brilliant successes for a record of aerial combat achievement unsurpassed in this war. Boldly searching out an approaching enemy force on January 25, Captain Foss led his eight F4F Marine planes and four Army P-38s into action and, undaunted by tremendously superior numbers, intercepted and struck with such force that four Japanese fighters were shot down and the bombers were turned back without releasing a single bomb. His remarkable flying skill, inspiring leadership and indomitable fighting spirit were distinctive factors in the defense of strategic American positions on Guadalcanal.