Lee Moves North

After their stunning victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his 72,000-man Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River and headed north into Pennsylvania.

With Lee in position to threaten major Northern cities, many feared that one more Union defeat might end the war in the South’s favor.

Faced with yet another failed commander, President Abraham Lincoln replaced Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker with Maj. Gen. George Meade. Meade began concentrating the 104,000 soldiers of the Army of the Potomac as he sought to locate Lee’s forces in Pennsylvania.

The First Day – July 1, 1863

The great battle started as a simple encounter between the lead elements of Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s Brigade marching down the Cashtown Pike towards Gettysburg and cavalry forces under the command of Union Brig. Gen. John Buford. Buford’s cavalry was able to delay the Confederate advance towards Gettysburg long enough for the Union I Corps to arrive west of town and the Union XI Corps to take positions to the north.

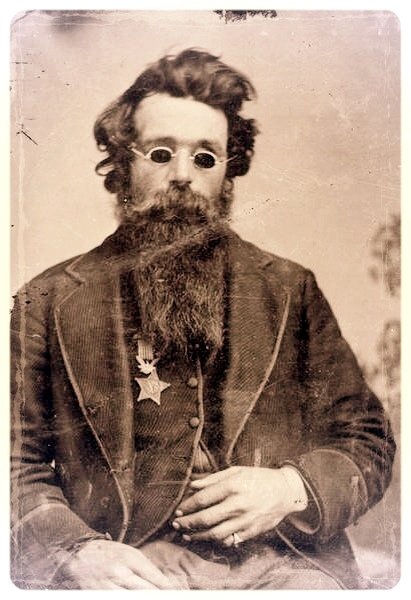

The Confederates continued to feed units into the growing battle, and soon heavy fighting could be found all along the Union line. Along McPherson’s Ridge and in the nearby Herbst Woods, the famed Union Iron Brigade fought a fierce battle against Confederates from Archer’s Brigade. Sergeant Jefferson Coates of the 7th Wisconsin was engaged in the intense firefight and would earn the Medal of Honor for his actions in this part of the battle. Coates managed to survive the maelstrom despite being shot in the face and losing sight in both eyes.

The Confederates continued to push the Union forces back towards Seminary Ridge. Around 11 am, the 6th Wisconsin Regiment was sent forward and advanced with the 95th and 84th New York Regiments against Mississippians and North Carolinians holding a line in and behind an old railroad cut. Corporal Francis Waller of Company I, 6th Wisconsin raced forward and engaged the color bearer of the 2nd Mississippi at the cut. Waller wrested the flag of the 2nd Mississippi away from their color bearer in the melee – an act that would later earn him the Medal of Honor.

Other Union regiments positioned near the McPherson Barn pivoted to confront an advance by North Carolinians at the Unfinished Railroad. Two men from the 150th Pennsylvania – Lt. Col. Henry Huidekoper and Corporal J. Monroe Reisinger – would earn the Medal of Honor for their actions at this point in the battle. Huidekoper refused to leave his command despite receiving a severe wound to his right arm, which was amputated after the battle.

Meanwhile, Confederate forces under the command of Maj. Gen. Jubal Early attacked the Union XI corps positions north of town. The Federal lines crumbled, and the Northern soldiers streamed back through town. Concerned over reports from the front, Meade sent forward Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock to take charge of the Union right. Hancock managed to stabilize the situation and build a new line atop Cemetery Hill – one of the strongest defensive positions on the battlefield. Confederate attacks against this position were handily repulsed later in the day.

Facing trouble on their right and increasing pressure to their front, the remainder of the Union I Corps fell back to Seminary Ridge as evening came to the battlefield. Throughout the night, both sides brought forward the bulk of their armies for what would prove to be an even deadlier second day.

Ten different Union soldiers would earn the Medal of Honor for their actions on this first day.

The Second Day – July 2, 1863

By the morning of the second day, Meade’s Army of the Potomac held a 3-mile line that resembled an inverted fishhook. The right was anchored on the wooded slopes of Culp’s Hill, and the Union line bent back around Cemetery Hill and Cemetery Ridge to its southern terminus at Little Round Top.

Building upon the first day’s successes, Robert E. Lee ordered Lt. Gen. James Longstreet and his corps to attack the Union left. As he had done masterfully at Second Manassas and Chancellorsville, Lee believed this flank attack would roll up the Army of the Potomac’s line.

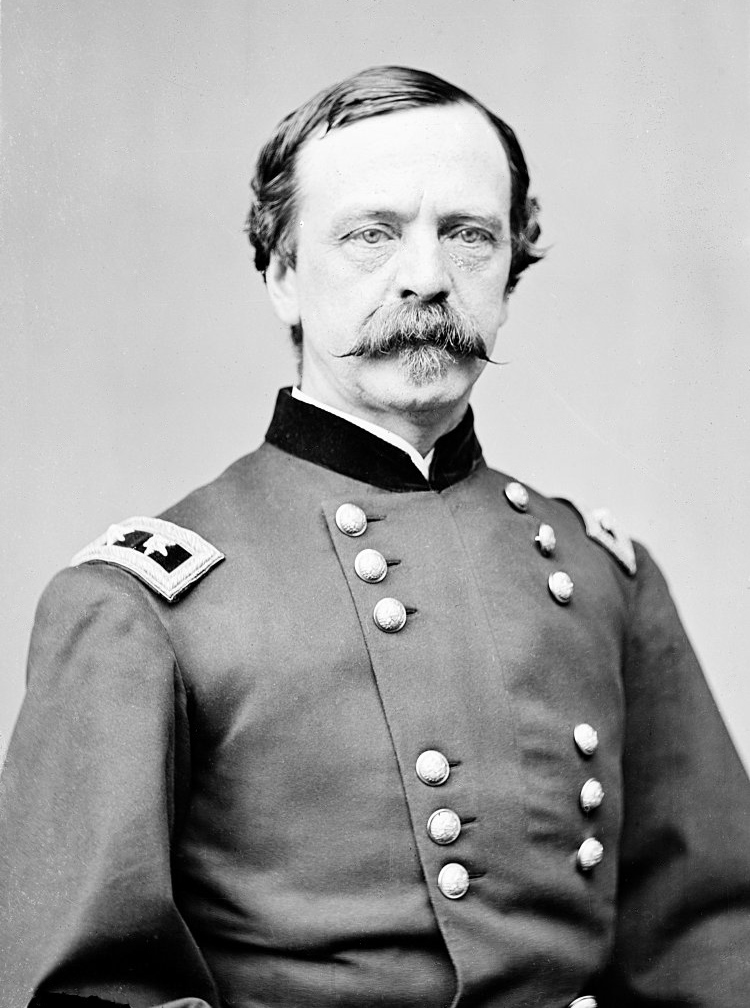

But before Longstreet’s assault got underway, there were already important changes on the Federal side that would affect the upcoming battle. Liberally interpreting his orders, Maj. Gen. Dan Sickles moved his Union III Corps forward from Cemetery Ridge towards high ground near a peach orchard on the Sherfy Farm. This advanced position created a dangerous salient that the Confederates attacked with full fury.

Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaw’s Confederate division struck Sickles’ forces in the Peach Orchard and Rose Farm. The Confederate assault devastated the III Corps, and Sickles, hit by a cannonball in the leg, was carried off the battlefield on a stretcher while smoking one of his trademark cigars. Despite the raging controversy caused by Sickles’s advance, the New Yorker would receive the Medal of Honor 34 years later for his actions at Gettysburg.

After the fierce fight in the Peach Orchard, the battle flowed into a region that became known as The Wheatfield. Savage back and forth fighting here was some of the bloodiest anywhere.

Following an intense artillery barrage, Confederates in Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood’s division charged towards two peaks they could see in the distance – Round Top and Little Round Top. It was here that Hood expected to turn the Federal army’s vulnerable flank. But unbeknownst to the Confederates, the Union army had also concluded that holding this ground was essential and had hastily positioned artillery and soldiers atop the heights.

Hood’s veterans first crashed into the rocky Devil’s Den and, in a fierce fight, drove back the Union forces. Medal of Honor recipient Sergeant Harvey May Munsell, color bearer of the 99th Pennsylvania, was stunned by an artillery shell atop Devil’s Den but held onto the flag even when his position was overrun.

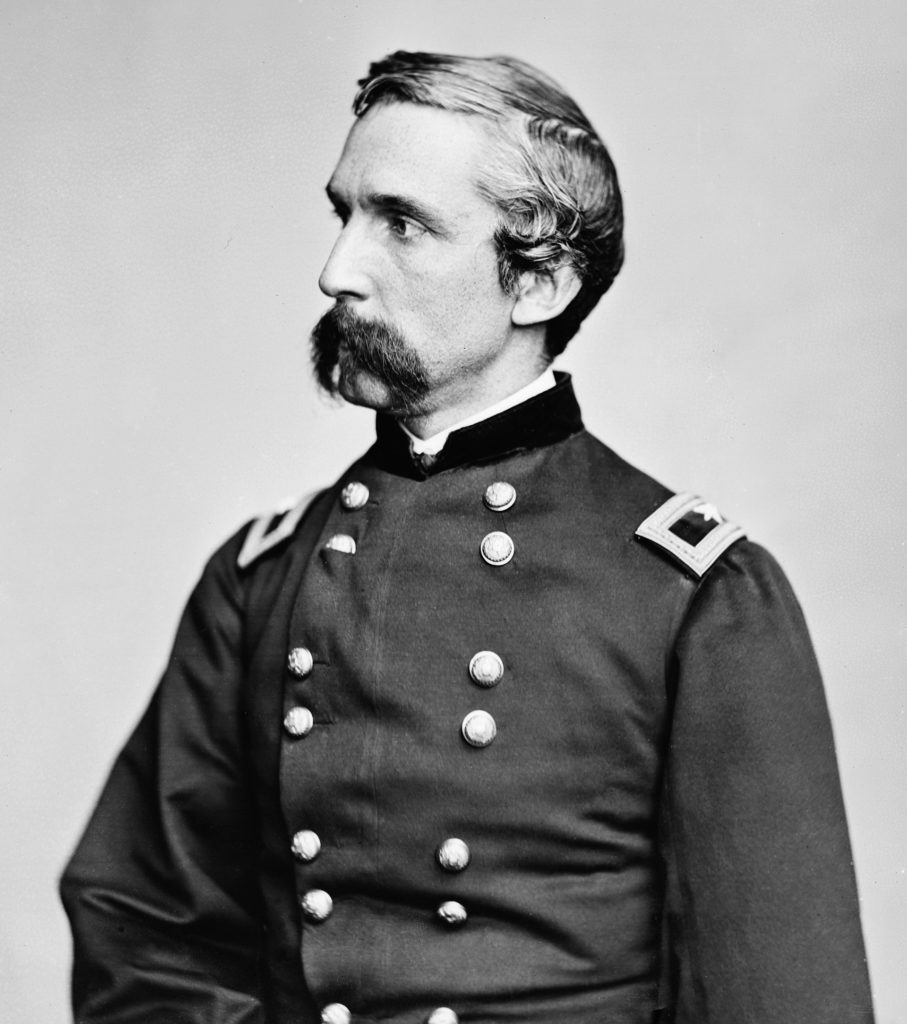

After seizing the Devil’s Den, Hood’s soldiers began advancing up the steep slopes of Little Round Top. But instead of finding an empty hilltop, the Confederates were met with a blaze of cannon and rifle fire by Union regiments. One of the regiments rushed to the rugged mountain was the 20th Maine under the command of Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain.

In what would become one of the more famous actions during the battle, Chamberlain’s men faced repeated attacks by Alabamians under the command of Lt. Col. William Oates. Despite suffering heavy casualties and being nearly out of ammunition, Chamberlain gave the fateful order to fix bayonets and to charge down the hillside into the oncoming Confederate assault. The unexpected Union charge stunned the Confederates and secured the Union left. Both Chamberlain and Sergeant Andrew Tozier from the 20th Maine would later receive the Medal of Honor for their actions at Little Round Top.

Longstreet’s assault on the Union left, and Ewell’s attack on the Union right at Culp’s Hill had nearly succeeded. As night fell on the corpse-strewn battlefield, Meade declared the fighting at Gettysburg to be “one of the severest contests of the war.” But rather than retreat, as many of both sides thought he would, Meade made the fateful decision to “remain in my present position to-morrow.”

Twenty-two different Union soldiers would earn the Medal of Honor for their actions on the second day of the battle.

The Third Day – July 3, 1863

Despite the heavy casualties incurred so far, Robert E. Lee remained confident that victory was at hand on the third day. After forcing Meade to move forces to the threatened flanks, Lee believed that the Union center must now be his enemy’s weak spot. With the arrival of Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s division, Lee had a fresh, new force to lead this final assault. The Confederate cavalry under the command of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart would support the attack with their charge from the rear.

Around 1 pm that hot afternoon, more than 150 Confederate artillery pieces let loose with an enormous cannonade against the Union lines on Cemetery Ridge. At around 3 pm the artillery fire subsided, and 12,500 Confederates soldiers began their mile and a half advance across the farm fields. As the Confederate force crossed the Emmitsburg Pike, they were lashed by Union artillery and rifle fire.

Pickett’s Virginians aimed their advance for the “Copse of Trees” a landmark that could be seen through all the smoke.

Those Confederates who survived crashed into Federal units under the command of Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock. At such a close range, Union artillery firing canister blew holes in the Confederate lines. 1st Lt. Alonzo Cushing commanded one Federal battery at the center of the Union line. Cushing received a severe abdomen wound in the fight, and two of his guns were knocked out. Cushing refused to be taken from the battlefield and kept his men firing at the advancing Rebels. Late in the struggle, Cushing was hit in the mouth by a Confederate Minié ball and was killed. One hundred fifty-one years after the battle, Cushing would posthumously be awarded the Medal of Honor – the only Gettysburg Medal of Honor recipient to die in the battle.

Brutal hand-to-hand fighting finally overcame the advancing Confederates. Corporal Joseph De Castro from the 19th Massachusetts joined in the intense melee and seized the colors from the color bearer of the 14th Virginia. De Castro’s bravery would later earn him the Medal of Honor – the first Hispanic recipient in our nation’s history.

Those Confederates that weren’t wounded or captured limped back to Lee’s lines at Seminary Ridge. The Confederate assault – Pickett’s Charge – resulted in a real debacle. Pickett’s division alone suffered more than 2,600 casualties or more than 50%.

The Confederate cavalry attacking the rear was met by Union cavalry and dealt a severe blow. That, combined with further losses on Culp’s Hill, convinced Lee that the game was up and the battle lost. Lee would order his defeated force back to Virginia.

And on the far Union left, Col. William Wells of the 1st Vermont Cavalry would earn the Medal of Honor for leading a daring charge against Confederate Brig. General Evander Law’s Alabama Brigade.

Thirty-two Union soldiers, equal to the first two days combined, would earn the Medal of Honor fighting Lee’s Confederates on this fateful day.

Medal of Honor Facts: The Battle of Gettysburg

- Of the 64 Battle of Gettysburg recipients, only 20 received their Medals of Honor during the Civil War.

- Corporal Joseph De Castro became the first Hispanic Medal of Honor recipient

- Lt. Alonzo Cushing received his Medal of Honor 151 years after he was killed at Gettysburg.

- Corporal Thaddeus Smith of the 6th Pennsylvania Reserves is the youngest Gettysburg recipient – he was 16 years old. He died in 1933.

- Only one of the 64 recipients died during the battle – Lt. Alonzo Cushing

- One bugler (Charles Reed) and one musician (Richard Enderlin) earned the Medal of Honor at Gettysburg.

Conclusion

Combined with the July 4, 1863 surrender of another Confederate Army in Vicksburg, Mississippi, Robert E. Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg would later become known as one of the turning points of the American Civil War. Never again would the Confederacy penetrate so deeply into Union land with such a significant force.

The human cost to both sides was enormous. The more than 51,000 casualties incurred in both armies would make Gettysburg the bloodiest battle of the war. Sensing the importance of the battle and the great sacrifice incurred, President Abraham Lincoln traveled to the battlefield. On November 19, 1863, he delivered his inspiring “Gettysburg Address” – one of our nation’s most important speeches.

Sixty-four soldiers earned the Medal of Honor for their actions at the Battle of Gettysburg – more than any other single battle in the Eastern Theater of the war. Of that total, only 20 would receive the medal during the Civil War. The rest would seek and receive this honor later in life. Many of the veterans in their later days sought recognition for their past deeds at Gettysburg. Applications and recommendations for the Medal of Honor poured into the War Department. Forty of the 64 medals were awarded between 1887 and 1905. The last Medal of Honor recipient from Gettysburg, Corporal Thaddeus Smith of the 6th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry, would die in March of 1933. And as mentioned above, the most recent Gettysburg recipient – the 64th – was Alonzo Cushing, whose award was approved by President Barack Obama in 2014.

Today we honor just one of those men, Lieutenant Alonzo Cushing, who, as Lincoln said, gave their “last full measure of devotion.” His story is part of our larger American story — one that continues today. The spirit, the courage, the determination that he demonstrated lives on in our brave men and women in uniform who this very day are serving and making sure that they are defending the freedoms that Alonzo helped to preserve.

President Barack Obama at 1st Lt. Alonzo Cushing’s 2014 Medal of Honor ceremony