November 11, 1921, marks the centennial of the entombment of the Unknown Soldier—a Medal of Honor recipient—at Arlington National Cemetery. Three years after the end of World War I, Americans had only begun to cope with their memories of that conflict, in which four million Americans put on a uniform and one million experienced combat, with over 53,000 of those loving their lives in combat. The Unknown Soldier came to symbolize those sacrifices.

Preparations for the identification of the Unknown Soldier were highly ritualized and elaborate, reflecting the impassioned feelings of the American people in the aftermath of their first modern global war. On October 24, 1921, after a random selection process, Sergeant Edward F. Younger, son of German immigrants and a Chicago postal worker, chose America’s Unknown Soldier. He did so by laying a wreath of roses on one of four coffins containing unidentified remains of doughboys killed in action on different parts of the Western Front, including the Meuse-Argonne. A short time later the coffin was loaded on a ship to be carried home for burial in Arlington National Cemetery.

The ceremony would be vast and ornate, perhaps unlike any public event in American history since President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral in 1865. Hundreds of thousands if not millions of spectators were expected, including newly elected president Warren G. Harding, former President Woodrow Wilson, hundreds of civilian and military officials, thousands of veterans, thousands of war mothers and wives, and hundreds of Medal of Honor recipients from many wars. Decorated heroes would be given pride of place in the ceremony—behind politicians and generals, of course. Eight would serve as pallbearers. Dozens more would be honorary pallbearers, not actually carrying the coffin but following it and joining a select group at the graveside.

Only one man, though, would represent the United States infantry and all living servicemen, thus taking pride of place among the veterans at the ceremony. Unlike the randomly chosen Unknown Soldier, Pershing would select this individual, whom the media would dub America’s greatest living military hero. As the final days of October passed, newspapers indulged in speculation. Many assumed the soldier would be Alvin York, or maybe even Pershing himself. They were wrong. On November 1, Pershing announced his choice: Sergeant Samuel Woodfill of the 5th Division, United States Army.

Born on an Indiana farm near the Kentucky border, Woodfill was a woodsman and a marksman. He had joined the army at age eighteen and stayed there, serving in Alaska (where he became a skilled big-game hunter) and along the Mexican border. In World War I Woodfill rose to the rank of captain and fought in the Meuse-Argonne. On October 12, 1918, he single-handedly demolished several enemy machine gun nests holding up his regiment’s advance and killed bunches of Germans with his rifle, his pistol, his bayonet, and a trench pick.

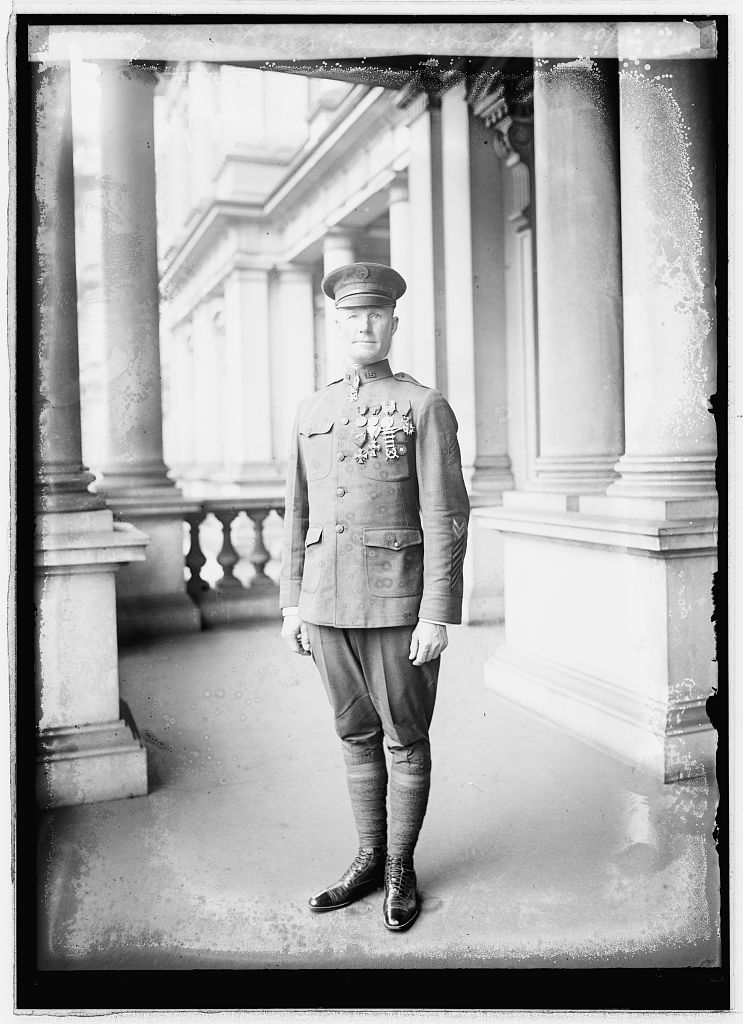

Woodfill received a Medal of Honor for these feats, even though the army returned him to the prewar rank of sergeant when hostilities ended. And Woodfill stayed in the army after reenlisting. Calm, erect, square-jawed, and well-spoken, he had not received much publicity to this point but had no trouble handling it when it came.

Newspapers immediately decided that Woodfill represented the “first” American. They pointed out that no one had given him the credit he deserved, although Woodfill himself was modest: “My only regret,” he said, “is that I could not have done more.” But he was also articulate. Although gruff and unemotional about his exploits, he willingly talked about them with reporters. The newspapers loved him.

Woodfill arrived in Washington, DC, on November 4, 1921. He was cheered by the House of Representatives and presented to the president. Five days later, after further tributes, Woodfill stood with Pershing at the dockside in the Washington Navy Yard to greet the ship Olympia, bearing the body of the Unknown Soldier. As he waited, Woodfill stood obligingly, stomach in and chest out, gaze inscrutable, while Secretary of War John W. Weeks fingered the medals decorating his tunic in front of whirring cameras. After the ship docked, Woodfill led the other seven pallbearers representing each branch of the service onto the deck, lifted the coffin, and carried it down to a waiting caisson. They walked alongside it through mist and rain, past silent crowds, to the Capitol where it lay in state for two days.

Vast crowds surged into Washington, DC, on the morning of November 11. Traffic jams prevented some outraged dignitaries from joining the ceremonies. At eight-thirty in the morning, Woodfill and the other pallbearers lifted the coffin from the Capitol’s dome room and carried it to the caisson. The assembled procession then moved slowly down Pennsylvania Avenue to the accompaniment of muffled drums and a funeral dirge. Walking alongside and immediately behind were the pallbearers, the president, Pershing, Chief Justice Taft, the House of Representatives, the Senate, and former president Wilson in his carriage. Harding and Pershing kept gesturing with their hands to urge the crowd to silence. In the cold and light mist, spectators stood attentive and bareheaded. From the Capitol steps, a ripple of grief passed through the crowd as mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters, wives and girlfriends, and children, broke down sobbing and fled, fell to their knees, or were led away.

The procession halted briefly in front of the White House so that the president could take his place in the reviewing stand. As it did so a group of generals and politicians crowded around Woodfill to congratulate him. But he saw nothing to celebrate. Fulfilling his role throughout with professionalism and profound respect for his comrades, Woodfill accepted his role but not once presented himself as a hero. Embarrassed and possibly offended, he acknowledged the generals’ and politicians’ plaudits only by standing stiffly to salute.

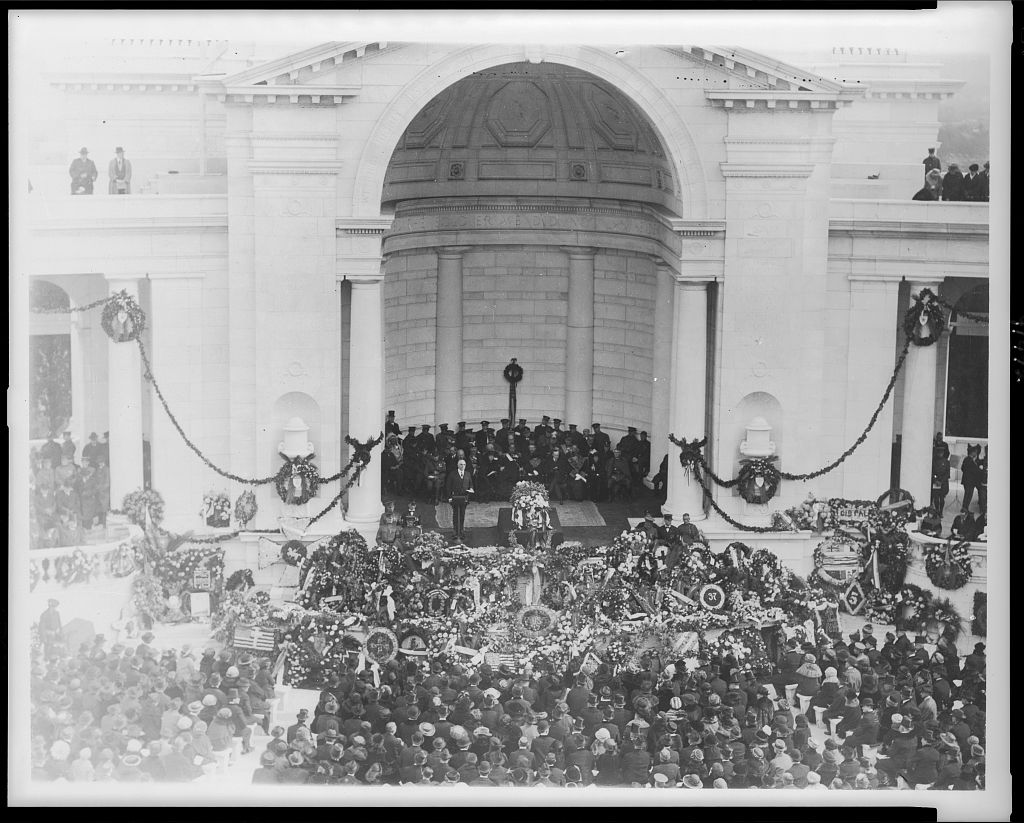

The procession, the marine band at its head playing Chopin’s Funeral March, reached Arlington Cemetery at eleven-thirty that morning. It continued past silent crowds to the right colonnade. From there pallbearers carried the casket before chiefs of the army and navy to the flower-decked amphitheater, filled with some five thousand honored guests including servicemen and -women in uniform. As the marine choir sang, the pallbearers placed the coffin on a bier in front of a platform on which stood a small assembly of honored guests: among them Vice President Calvin Coolidge and his wife, Grace; honorary pallbearers; and a Native American chief who would deliver the final blessing.

After more hymns, the marine band broke into the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Three aircraft circled the amphitheater in tribute. After a bugle call, the crowd observed two minutes of silence. President Harding arrived from the White House in a car, then rose to give a speech fit for the occasion. As he did so, the clouds broke and the amphitheater erupted in sunlight.

Harding spoke well and was broadcast on the radio. While testifying to the bravery of those who had and had not fallen, and espousing the cause for which they fought, he condemned war and hatred unequivocally. “This American soldier went forth to battle with no hatred for any people in the world,” he said, “but hating war and hating the purpose of every war for conquest. . . . In advancing toward his objective was somewhere a thought of a world awakened, and we are here to testify undying gratitude and reverence for that thought of a wider freedom.” The president concluded: “It is fitting to say that his sacrifice, and that of the millions dead, shall not be in vain. There must be, there shall be, the commanding voice of a conscious civilization against armed warfare.”

After a few more hymns, the pallbearers bore the coffin to the hill followed by a procession of admirals, generals, princes, and potentates. With the Capitol in view, the Unknown Soldier entered his final resting place. A Christian graveside service followed. A selected procession of mothers and other honored guests laid wreaths and tributes beside the mausoleum. Finally, a western Native American chief in a magnificent bonnet conducted a Native American rite of burial. He concluded by laying his bonnet on the coffin. The ceremony ended with taps, and rifles firing a military salute.

Today, the Unknown Soldier, attended by the Honor Guard, continues to pay silent testimony to America’s fallen of all wars.

Edward G. Lengel, Ph.D. This article was excerpted in part from Lengel’s book Never in Finer Company: The Men of the Great War’s Lost Battalion (2018).