August 5, 1864

A Daring Plan

Possessing the far larger and more capable navy, the Union sought to use its naval power to cut off all Confederate access to the sea through a coastal blockade. Despite continued Federal efforts, several key ports remained open to Confederate blockade runners bringing important military supplies. One of those ports, and the only one remaining on the Gulf Coast in 1864, was the port at Mobile, Alabama.

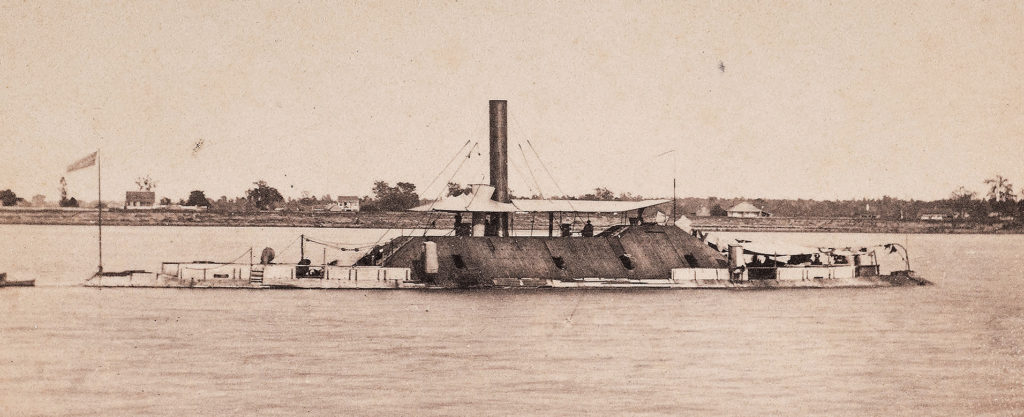

After the successful capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in July of 1863, the Union naval forces in the western theater were freed for use against Mobile. Despite growing Union naval resources, the Confederate defenses guarding Mobile Bay were formidable. Not only would the Union fleet have to overcome several powerful forts guarding the bay’s entrance, but once inside the bay, there were reports that the Confederates had built and deployed a new ironclad warship named the CSS Tennessee. This ship and the others gathered by the Confederates were under the command of Admiral Franklin Buchanan – the same man who had commanded the CSS Virginia (Merrimac) at the historic Battle of Hampton Roads in 1862.

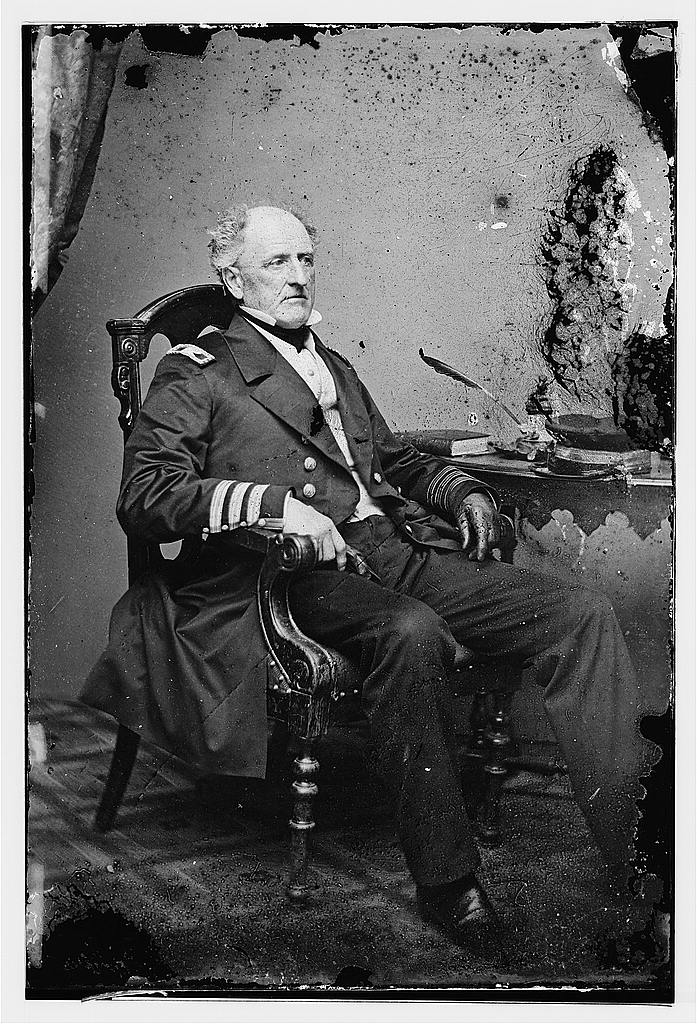

Undeterred by these challenges, Rear Admiral David Farragut prepared to push his fleet of 18 warships quickly through the narrow channel between Fort Morgan and its 46 heavy guns and a field of underwater mines. Speed and determination would be required to get his vulnerable ships past Fort Morgan and into the bay. Once there, Farragut planned on using his ironclads and wooden, steam-powered warships to overwhelm the Confederate naval forces.

“Damn the Torpedoes!”

The morning of August 5, 1864 dawned with near-perfect conditions for Farragut to unleash his attack. With the tide running into the bay and a southwest breeze likely to blow smoke into the faces of those operating the big guns at Fort Morgan, Farragut gave the signal to advance in column down the narrow channel.

Leading the assault were his four ironclads – USS Tecumseh, USS Manhattan, USS Winnebago, and USS Chickasaw. Tecumseh fired the first shots at approaching Confederate naval vessels at 6:47 am, and others behind the Tecumseh fired at Fort Morgan. The Tecumseh continued past the fort when it struck one of the underwater mines (called torpedoes in the Civil War) and promptly sank in full view of the rest of the ships. This sudden disaster could have unnerved the Union fleet, but Farragut remained undeterred. And while his exact words may have been different, Farragut’s exclamation – “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead” – has gone down in United States Navy lore.

With many of the more vulnerable wooden ships lashed together for protection, the remaining Union ships continued to press forward while shot and shell from the fort and other Confederate naval vessels peppered the Federal warships. Aboard his flagship USS Hartford, Farragut prepared to shift his attention to the iron monster moving slowly towards him at the end of the channel.

Duel with the Tennessee

Despite being outnumbered 18 to 4 in ships, Buchanan’s plan was a simple one. The powerful CSS Tennessee would meet head-on any Federal ships that somehow survived the mines and the heavy guns of Fort Morgan. Just as he had done at Hampton Roads in 1862, Buchanan intended to ram and sink every ship flying the Stars and Stripes. However, unlike his duel with the USS Monitor in 1862, Buchanan and the Tennessee would simultaneously face three Union ironclads and other faster, more maneuverable steam-powered warships. The lumbering Tennessee did prove near invulnerable to Union shells and rams, but her slow speed made it near impossible for her to sink any of Farragut’s faster ships.

With most of the other smaller Confederate vessels now sunk, grounded, or driven off, Farragut’s fleet circled the great Rebel ironclad as a final act. With its smokestacks now destroyed and its steering chains shot away, the Tennessee sat near motionless in the bay. Continued fire, including entire broadsides from as close as 10 feet, battered and bent the Tennessee’s iron armor plates. One shell sent shrapnel flying through the interior of the Tennessee, breaking Admiral Buchanan’s leg. With the Chickasaw, Monongahela, Lackawanna, Hartford, and Ossipee pounding away at his crippled flagship, Buchanan gave the signal to surrender the Tennessee to Farragut and the Union navy.

With the Union forces now in control of the bay, Federal soldiers were subsequently landed to take the two prominent forts near the mouth of the bay, which they completed by August 23, 1864. The victory at Mobile Bay would be one of the signature achievements of Farragut’s storied career and one of the most celebrated naval actions of the Civil War. With this victory at Mobile Bay, only one significant Confederate port remained open at Wilmington, North Carolina.

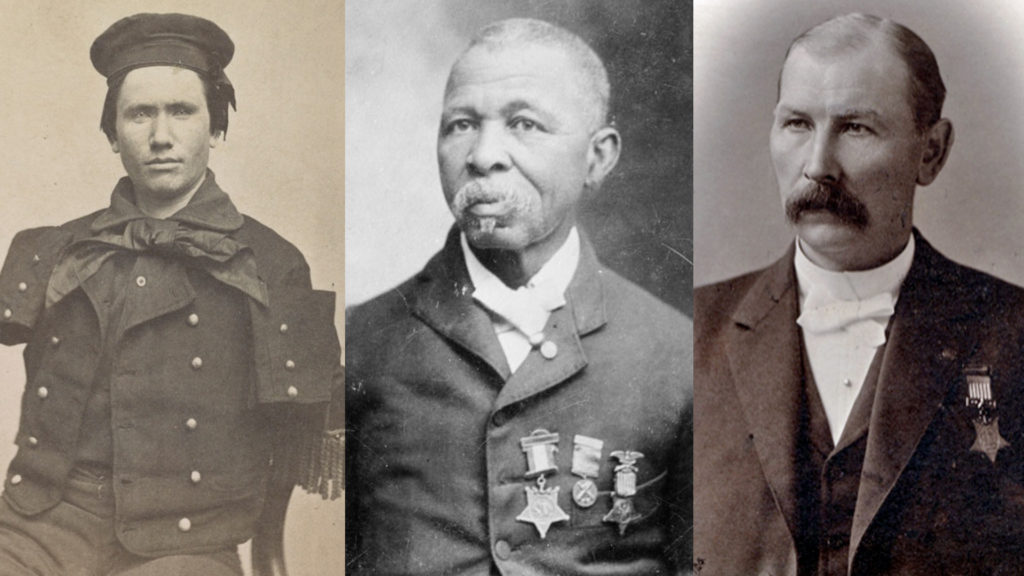

97 Medals of Honor

Farragut’s fleet at Mobile Bay suffered 150 killed and approximately 170 wounded in the battle. This was opposed by 13 dead and 26 wounded on the Confederate side. Despite the relatively low casualties, the victory at Mobile Bay was of great strategic consequence and greatly affected morale on both sides. Ninety-seven enlisted enlisted sailors, Marines, and landsmen would be awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions in this naval battle – more than any other battle in American naval history. Considering the large number of recipients from this battle, one must consider that during the American Civil War, the Medal of Honor was the only combat decoration available.

Per the law that created the Navy Medal of Honor in 1861, only “petty officers, seamen, landsmen, and marines” were eligible for the Medal of Honor at this time. In lieu of medals, Union naval officers deserving of recognition were mentioned in Farragut’s dispatches to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. In his detailed report sent to the Navy Department on August 12, 1864, Farragut noted “the terrible effects of the enemy’s shot and the good conduct of the men at their guns, and although no doubt their hearts sickened, as mine did, when their shipmates were struck down beside them, yet there was not a moment’s hesitation to lay their comrades aside and spring again to their deadly work.” In a subsequent report, General Orders Number 45, dated December 31, 1864, most of the Medal of Honor recipients from the battle were detailed. Within the list of recipients, you will find men from a wide variety of enlisted ranks and roles – ship’s cooks William Blagheen and James Mifflin, a “Boy” such as 16-year old James Machon, Coal Heavers such as William Madden and Richard Dunphy, Quartermasters like John Brazell, and Landsmen such as John Lawson. The last of the recipients to be awarded the Medal of Honor for the Battle of Mobile Bay were Ordinary Seaman Bartholomew Diggins and Landsman William Brown, who were both notified in 1891. And as indicative of the times, many of the Mobile Bay Medal of Honor recipients were first-generation Americans, having been born in countries as Norway, Ireland, Germany, Sweden, Canada, Denmark, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.

On board the flagship U.S.S. Hartford during successful attacks against Fort Morgan, rebel gunboats and the rebel ram Tennessee, Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. With his ship under terrific enemy shellfire, Dunphy performed his duties with skill and courage throughout this fierce engagement which resulted in the capture of the rebel ram Tennessee.

Medal of Honor Citation for Coal Heaver Richard D. Dunphy

Also true to the period where medals were mostly awarded to the living, all 97 Medal of Honor recipients from the Battle of Mobile Bay survived the battle. Many of the recipients would go on to live long lives, with the last, Quartermaster Thomas Jordan, dying in 1930 in Baltimore, Maryland.

Recommended Books

- West Wind, Flood Tide: The Battle of Mobile Bay by Jack Friend

Battle of Mobile Bay References

- Battle of Mobile Bay – Official reports of Rear Admiral David G. Farragut (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- ‘Go Ahead, Go Ahead’ (Naval History Magazine)

- Mobile Bay (American Battlefield Trust)

- Map: Battle of Mobile Bay (American Battlefield Trust)