By Clint Hayes

In the four months following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces swept east and south through the Pacific at will, occupying Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, Philippines, and the small island chains of the western Pacific.

By summer 1942, only lower Papua New Guinea stood between the Land of the Rising Sun and the Land Down Under. The Japanese juggernaut stood on Australia’s doorstep.

It would never advance farther. In the air, the 22nd Bombardment Group, flying the unfairly maligned B-26 medium bomber, played a large role in stopping the Japanese advance. Helping to push it back were the heavy B-17s of the 43rd Bombardment Group, a group whose existence was unknown to General George Kenney upon his arrival in Australia to take command of Allied bomber forces. Such was the state of affairs in the Southwest Pacific theater, a largely forsaken backwater hanging on the end of a supply chain stretching across a third of the globe.

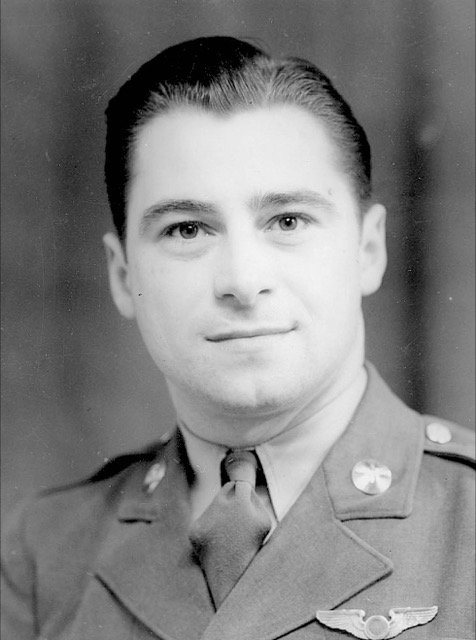

JAY ZEAMER JR.

(USAAF)

An unlikely player in both the 22nd and 43rd, considering the vast difference between the two bombers, was Lt. Jay Zeamer Jr. Son of an international salesman, Zeamer grew up in the shadow of New York City before graduating Culver Military Academy and MIT as a civil engineer. Soon after assignment to the 43rd at Langley, Zeamer was transferred to Wright Field to help flight test the new Martin B-26. He would spend the next fourteen months in the plane with the 22nd Bomb Group, from peacetime into combat in the Southwest Pacific.

JOSEPH R. SARNOSKI

(USAAF)

Sarnoski was in many respects Zeamer’s opposite, the fifth of sixteen children born to a miner and housewife who hunted and grew much of their own food in the coal fields of Pennsylvania. While Zeamer was the quiet, amiable, imperturbable engineer, Sarnoski was gregarious, ambitious, with little tolerance for fools or incompetence. But both, from childhood, shared a prodigious self-discipline and drive, and a dream—to fly.

Using the Civilian Conservation Corps as a bridge from the farm to the Army Air Corps, Sarnoski attracted enough notice as a ground crewman at Langley to be sent to Colorado for training as an aircraft armourer. He excelled in the role, enough to be selected as one of the first to participate in a program to train enlisted bombardiers. Soon Sarnoski was putting on practice bombing displays for the AAF brass and teaching gunnery throughout the 2nd Bomb Group. One of his students was Jay Zeamer. An instant friendship formed, but with Zeamer’s transfer to the 22nd, it would be over a year before they met again, and half a world away.

It took Zeamer’s finagling his own transfer in Australia, this time into the B-17s of the 43rd BG—by fate into Sarnoski’s squadron—and the loss of Sarnoski’s pilot to enable them to join forces. They handpicked a crew that appreciated their zeal for preparation, Sarnoski’s strict training, and Zeamer’s confident flying. But it was Zeamer’s constant volunteering that would inspire their nickname—Zeamer’s “Eager Beavers.”

TARGET: RABAUL

(USAAF)

The linchpin of all Japanese activity in the southwestern theater was Rabaul. The formidable port on New Britain’s easternmost tip allowed Japan to dominate the Solomon Sea, Solomon Islands, and most of New Guinea.

An essential part of the Allied plan to nullify Rabaul was the capture of Bougainville, largest island of the Solomon chain. Essential to its capture were accurate topographical maps.

An order for a photo-mapping mission of the island went out in May 1943. Such missions were already dangerous, lacking fighter support and requiring straight and level flight for extended periods of time at high altitude. This one would be especially so: a 22-minute run in enemy territory, a mere hour from Rabaul itself, and 580 miles from home—just shy of the distance from London to Berlin. Consequently, it was treated as a volunteer mission.

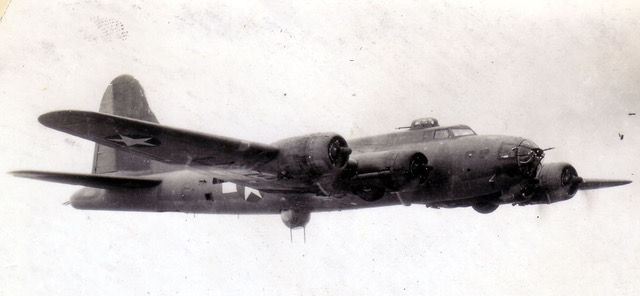

“666”

(Courtesy Dan Johnson / Larry Hickey)

It also required a specialized aircraft, equipped with a three-camera array installed in the bottom of the plane that, taken together, could create a seamless, sixteen-mile wide map of the target area.

Now squadron executive officer and wanting to fly more, Zeamer had recently requisitioned one such plane, B-17 #41-2666, for his own crew’s use. Already experienced at such missions and knowing the risks, Zeamer immediately volunteered for the job and set his crew to customizing “666” for it.

All unnecessary weight was removed and all four engines replaced. For extra protection, Zeamer added three more .50 calibers to the normal thirteen found on Southwest Pacific B-17s: one in the nose beneath the bombardier’s deck that he could fire himself, and two more in the waist by replacing the single .50s with twins—a remarkable feat of field engineering and unique in the Pacific theater.

GREEN LIGHT

Weather delayed the mission for months, but on June 15, a B-17 from the 8th Photo Recon squadron attempted it. When its cameras failed, the call went to Zeamer. He and the crew spent the day making last minute preparations and lining up substitute personnel.

Two regular crew members, copilot Lt. Hank Dyminski and flight engineer Sgt. Bud Thues, were grounded with malaria. Taking Dyminski’s place was his friend Lt. J.T. Britton. Assistant flight engineer Sgt. Johnnie Able, normally belly turret gunner, would sub in the top turret for Thues. Squadron armaments chief Sgt. Forrest Dillman would replace Able in the belly turret. Sarnoski, now a lieutenant after a field commission, was scheduled to rotate home in three days. He volunteered anyway.

That night Zeamer received a call from Bomber Command adding a recon of Buka airstrip, off Bougainville’s northern tip, to the mission. Zeamer refused, citing the risk of stirring up a hornet’s nest prior to mapping.

16 JUNE 1943

(Courtesy Clint Hayes / mapcarta.com)

Take-off from Port Moresby was at 4:30 a.m. on the 16th. As ‘666—now named “Lucy” after Zeamer’s Langley girlfriend—taxied to leave, a jeep stopped them with written orders for the Buka recon. Zeamer again refused.

Plans changed when they arrived at Bougainville half an hour early; the sun was too low to provide the needed topographical relief. Zeamer put the choice to the crew: burn half an hour over the ocean or do the Buka recon. The crew voted unanimously for the recon.

In a grim surprise, rather than the few green army Zeros they’d encountered before, the airfield was packed with gray navy A6M3 Zeros. They belonged to the veteran 251 Kokutai, sent south to Buka from Rabaul just the day before for an attack on Guadalcanal scheduled for that afternoon. An enemy recon couldn’t be tolerated.

The crew counted seventeen Zeros taxiing or taking off. Japanese records show eight ultimately engaging the lone B-17. Zeamer knew it would take them most of the mapping run to catch the bomber, and that it could be days or weeks again before the weather agreed. They would continue to the primary mission.

The first twenty minutes went smoothly, if tensely, as the crew watched the Zeros climbing to intercept. Shortly before the end of the run, two ineffectual passes were made on the B-17 from below, but those in the front could see several forming up to consolidate on the front. These were experienced pilots. The crew in the back reported two more coordinating from the rear left and right. The Fortress was being surrounded for a simultaneous assault.

Zeamer quickly assessed. He would certainly be excused for breaking off the mapping under the circumstances, but he knew that Empress Augusta Bay, now below them, was the primary objective of the mapping. Without it, yet another crew would have to attempt the same mission. They would just have to shoot their way out. It was, after all, why they’d outfitted ‘666 the way they had. Zeamer told the crew to prepare to shoot their way out.

The initial attack is a confusion of memories, even in contemporary crew accounts. Taken together, though, it seems clear there were two coordinated attacks on the nose of the plane, a vertical and horizontal, by three Zeros, though in which order is unknown.

The combined fire of the forward guns caused most of these attackers to break off, with navigator Lt. Ruby Johnston manning both cheek guns as necessary. But at least two Zeros pressed their attacks long enough to ravage the nose. Sarnoski was wounded in the neck by a 7.5mm bullet but kept firing. Soon after, a 20mm cannon blast in the nose blew both him and Johnston from their guns, Sarnoski to the floor with a gaping wound in his side, Johnston back beneath the flight deck with shrapnel in his face, shoulder, side, and back.

At least two more 20mm shells struck, one behind the pilot’s seat which ignited the oxygen supply, and yet another in the nose, this time on the back of the flight deck at Zeamer’s feet. That explosion not only blew out Zeamer’s instrument panel and wrecked his rudder pedals, it shattered his left knee, exposing bone, and filleted his legs and arms with shrapnel. A gash on his right wrist made his control wheel slippery with blood. Miraculously, Britton, the substitute copilot, was unhurt.

And still the nose was under attack. A Japanese “Irving” on its own recon mission had seen the melee and decided to join. Zeamer feared the worst, but through a hole in the bulkhead, he could see his mortally wounded bombardier climbing with great effort back to his gun. Sarnoski drained what was left of his strength into the closing fighter, persuading it to break off before it could deal a potentially fatal blow to the cockpit. He then collapsed onto the bombardier’s deck.

For the moment the Fortress was in the clear. Photographer and waist gunner Sgt. George Kendrick had confirmed the photography was complete, and the two Zeros in back had been brushed aside by him and the other rear gunners, though one had grazed radio operator Sgt. William Vaughan in the neck. The crew heard Vaughan exclaim, then laugh and confirm he was okay. It was the last time the interphone would work.

But the oxygen fire still burned. Johnston, half-blind from blood, crawled from the nose to put out the fire with his hands and nearby rags, suffering burns on both arms. The lack of oxygen prompted Zeamer to shove the B-17 into a steep turning dive. Without the interphone, none could know the fate of their pilots or plane, yet not a single crew member left his station.

With Britton’s help, Zeamer coaxed ‘666 out of the dive around 10,000 feet. Unfortunately every Zero had followed them down. The crew watched helplessly as the Japanese lined up on either side of them, beyond their range, to take turns making passes on the front. The enemy clearly believed ‘666 was now completely exposed from the front. They were right: all of the front guns were inoperable. Zeamer’s only recourse was to outmaneuver his enemies. Everything he’d ever learned in fifteen months of combat was now being put to the test.

For the next forty minutes, without morphine, with a broken leg and boots filling with blood, Zeamer wrenched the plane back and forth, pass after pass, banking inside each Zero’s fixed line of fire and forcing it to miss. From experience and frequent strategy sessions, it was a familiar maneuver to the gunners in back, who raked each Zero in turn as it rolled past. Despite the unending attacks, the agile, unyielding defense prevented any more serious damage.

Finally it proved too much. With one Zero in the water, another struggling home, and the rest low on fuel and ammunition, the frustrated Japanese gave up and returned to Buka.

Zeamer and Britton took stock. It was clear Zeamer and Sarnoski wouldn’t last a return trip over New Guinea’s mountains to Port Moresby. Instead they would try for Dobodura, a newer base on New Guinea’s east coast, itself three hours away. Fortunately they still had four good engines, but no flaps or brakes, only the airspeed indicator and magnetic compass for flight instruments, damaged control cables, and Zeamer’s smashed rudder pedals.

Zeamer himself was somehow still conscious, and still refusing to be moved or receive morphine. He insisted the others should come first.

Britton had Able, though wounded in both legs, take the copilot seat, justifying Zeamer’s insistence that every crew member learn the basics of flying the plane. Britton bandaged Zeamer as well as possible, then did a tour of the bomber. In the nose he helped Johnston and Sarnoski, who was then clinging to life, to the floor. In the back, fortunately, only Vaughan had been injured. Tail gunner Sgt. Herb “Pudgie” Pugh, close friends with Sarnoski, came to the nose to assist. It was in his lap that Joseph Sarnoski would pass away.

Lapsing in and out of consciousness, Zeamer provided guidance to Able, but could use only the sun and landmarks for direction to Dobodura. With their navigator sidelined, Vaughan had taken up the problem. Holding a rag to his wounded neck, using an undamaged spare radio he’d brought along for emergency purposes, Vaughan used bearings from multiple bases to narrow down their location and his best estimate for a heading. He relayed it to the cockpit, where Britton had resumed as copilot, and returned to his radio to keep Dobodura updated on their status.

His estimate was almost dead-on. Able stood behind and between the pilots to help secure Zeamer. Emergency vehicles stood ready at the airstrip, knowing ‘666 would be landing fast. Britton cut the engines before landing to help slow the plane, but it wasn’t enough. Approaching the end of the 6000-foot runway, he steered the plane into the sand in a wide turn until it came to a stop, sporting a reported five cannon holes and 187 bullet holes. Entering the plane, one medic said to wait to move the pilot because he was dead. It was a misunderstanding from the radio communications, but still drew a sharp response.

AFTERMATH

Zeamer lingered near death for three days after being returned to Port Moresby, requiring four blood transfusions and an estimated 120 pieces of metal removed from his body. He spent the next nine months in and out of hospitals in Australia and the U.S., and would use a cane for the rest of this life.

Sarnoski was buried soon after their return with the whole squadron in attendance, including all of the crew members save the still-hospitalized Johnston and Zeamer. It would be a week before Zeamer learned of his friend’s death.

Their sacrifices weren’t were in vain. The mapping was a success, and the photos obtained from it were used to generate the maps used in the successful Marine landing on Bougainville—at Empress Augusta Bay—the following November.

In his memoir of the war, General Kenney wrote that the 16 June 1943 mission over Bougainville and Buka “still stands out in my mind as an epic of courage unequalled in the annals of air warfare.” For their courage and sacrifice above and beyond the call of duty, Zeamer and Sarnoski both received the Medal of Honor, while the rest of the crew each received the Distinguished Service Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor.

They remain the most highly decorated single air crew, and solo air mission, in American military history.