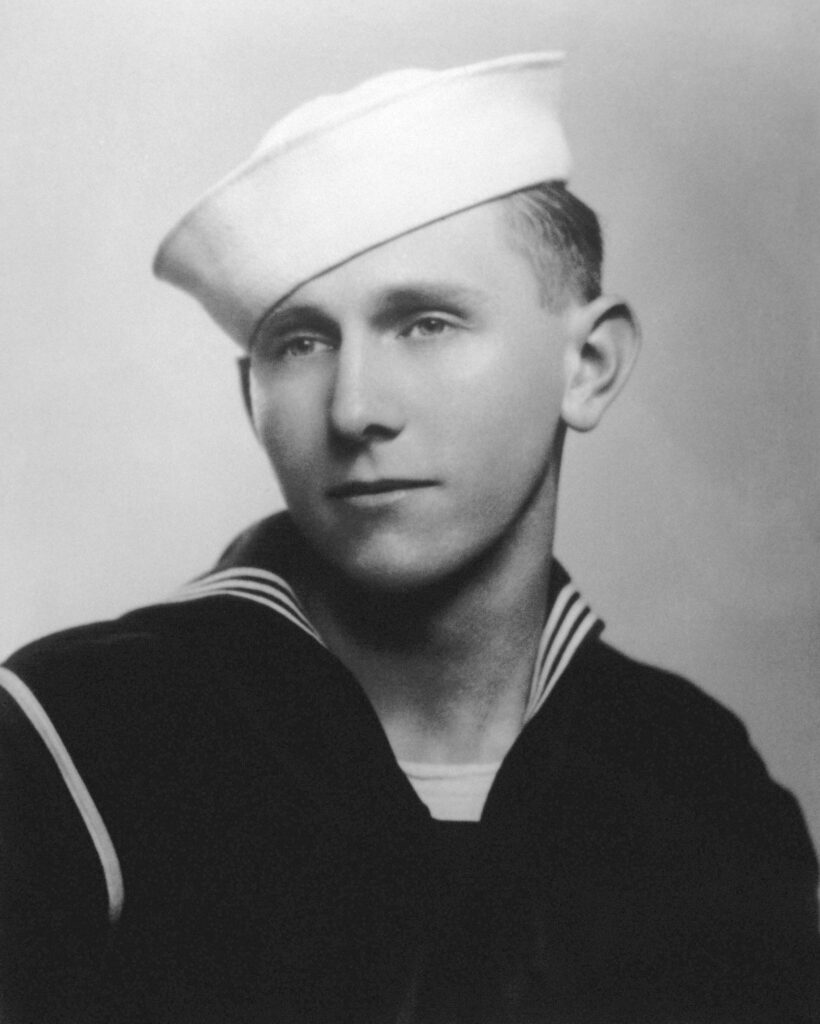

Meet Signalman First Class, Douglas Munro

From an early age, Douglas Munro had a passion for helping people. During the Great Depression, his father James held a steady job in Cle Elum, Washington, and grateful for the provision, Munro split wood and took it to less fortunate families in the area so that they could heat their homes during the harsh winter.

After graduating from Central Washington College, Munro longed to do something exciting. He applied to the Coast Guard and enlisted on September 18, 1939. That same day, Raymond Evans enlisted. The two formed an immediate friendship and were virtually inseparable (except for a brief time when they were assigned to different ships). This earned them the nickname “The Gold Dust Twins.”

The pair were selected to be crew members on the USCGC Spencer and learned how to navigate, keep a log, and maintain equipment. They studied to become signalmen and eventually earned the promotion. When the U.S. entered World War II in December 1941, Munro and Evans knew it wouldn’t be long before they joined the action.

Mixed Signals and a Miraculous Rescue

On August 7, 1942, American troops were stationed in Guadalcanal, Tulagi, in the Pacific.

Aboard the USS McCawley, Signalman First Class Munro safely transported several Marines to the island before grabbing his signalman’s gear and setting up camp for the night on the beach. In the dark hours, he carefully conveyed messages to American ships at sea via blinker light communication.

The next morning, he ferried wounded soldiers back to the McCawley. He learned that he was transferring to a boat pool at “Cactus,” which was a code word for Guadalcanal. Munro was joyfully reunited with his best friend, Evans, on the island; the inseparable Coast Guardsmen were glad to see one another again. Over the next few weeks, they continued to transfer injured comrades to the ships at sea, rescue airmen who were shot down from the sky, and move supplies.

On September 27, 1942, orders were given to send three companies of 1st Battalion, 7th Marines to land just west of Point Cruz. The hope was to attack enemy fighters from the rear, as they had been getting too close to American forces. Munro led a fleet of 24 Higgins boats to take the Marines to shore. After a safe landing, Munro and Evans returned to Lunga Point to refuel, but they received orders to turn around—the Marines they had dropped off were to be picked up immediately.

With Munro excitedly leading the way, the fleet sped to recover the soldiers. Upon arrival, they came under enemy fire. Refusing to leave his fellow Marines stranded, Munro expertly positioned the boat so Evans could cover the Marines as they boarded. After the last man was loaded, Munro turned for Lunga Point. Noticing another boat stuck on a reef, Munro pulled alongside it. With help from the Marines, they freed the landing craft.

Evans spotted waterspouts—enemy fire was getting close to the boat—and he yelled over the engine noise for Munro to duck. But it was too late. Evans watched a bullet strike his friend, and Munro fell on the deck. Grabbing the wheel, Evans commanded the boat back to Lunga Point, where Munro mustered the energy to ask if the Marines had gotten back safely. Evans responded affirmatively, and Munro died. He was only 22 years old.

For his unwavering commitment to his comrades, and for service above and beyond the call of duty, Edith Munro accepted the Medal of Honor on her son’s behalf on May 24, 1943. Munro is the only Coast Guardsman to ever receive the Medal of Honor.

Turning Grief into Action

Following her son’s death, Edith was inspired to join the Coast Guard mere hours after accepting the Medal of Honor. At 48, the Coast Guard reluctantly allowed her to join. She asked to be treated like a normal recruit and completed basic training. Edith later commissioned in SPARS, which was the female reserve of the Coast Guard, and ran the Coast Guard Barracks in Seattle, Washington. In 1945, she was discharged as a lieutenant.

Munro’s best friend, Evans, continued to serve in the Pacific, and transferred to the USS President Polk as a signalman. He later earned the Navy Cross for his heroic actions on that fateful day alongside Munro. Evans continued to serve in the Coast Guard for the rest of his career. In 1962, he retired as a commander.

But he never forgot his best friend or Munro’s courageous, selfless sacrifice.

Evans wrote to the U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office, “Doug was a vital, outgoing young man … he was fun to be around and we had some great liberty times together. He was a hard worker and we studied together to become proficient as Coast Guard signalmen … [Douglas Munro’s Medal of Honor] was deserved and no one was more pleased than I to have a high endurance cutter, USCGU Munro, named after him. I hope there is always a ‘Munro’ in the Coast Guard fleet.”