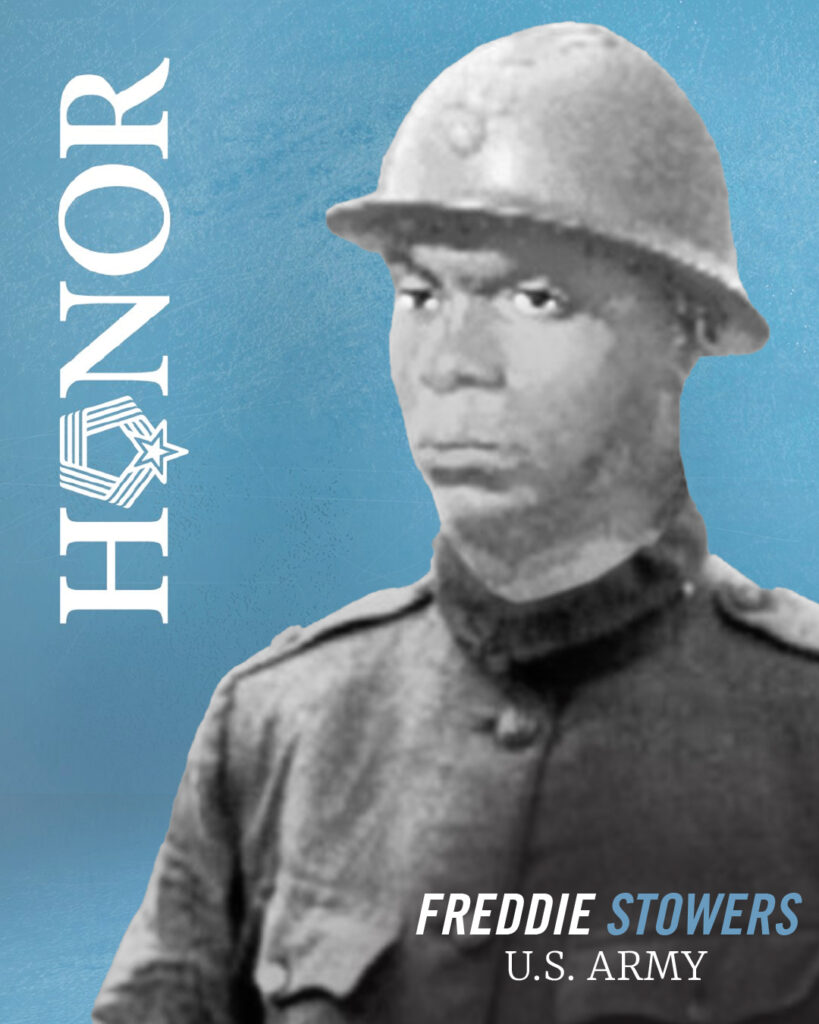

Meet Army MOH Recipient Freddie Stowers

Army Corporal Freddie Stowers grew up in Sandy Springs, South Carolina. His family was familiar with hardship and adversity. Stowers’ grandfather had been a slave, and Stowers, his parents, and his 11 siblings worked hard to run the family’s farm. He married a woman named Pearl, and they had a daughter, Minnie Lee. In 1917, Stowers was drafted and assigned to Company C, 1st Battalion, 371 Infantry at Camp Jackson, South Carolina. The all-Black regiment played a pivotal role in one of the deadliest battles of World War I.

Stowers’ Valiant Sacrifice

On the morning of September 28, 1918, Stowers and the 371st Infantry received orders to capture Hill 188 near Ardeuil-et-Montfauxelles in Ardennes, France, which was heavily occupied by enemy forces. Stowers and his comrades managed to evade machine-gun fire, mortars, and rifle shots, and the company continued its upward advance undeterred. Suddenly, German troops waived a white flag of surrender — but it was a false pretense. As American troops moved forward, German troops went back to their trenches and set off another round of machine-gun fire. About half of Stower’s company was mortally wounded or killed, including the officers, leaving 21-year-old Stowers in charge of the remaining men.

Mustering up his courage, Stowers bravely encouraged his comrades to continue fighting. They seized one German trench and silenced one machine gun. But there was more work to do. Stowers led his troops to the second German trench, but was struck by a German machine gun en route. Despite his fatal injuries, Stowers remained steadfast, rallying his comrades to move forward and complete their harrowing mission, until his last breath.

Stowers perished that day, alongside 133 other soldiers, and was buried at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial in France. Following the battle, Stowers and his company received the Croix de Guerre, France’s highest military medal. This extraordinary award is given to recognized supreme acts of valor committed by Allied troops. However, it would be more than 70 years before America would formally recognize Stowers’ incredibly bold acts of courage and sacrifice.

A Long-Awaited Medal

After the battle, Stowers’ commanding officer nominated him for the Distinguished Service Cross, which was later upgraded to the Medal of Honor. Unfortunately, the administrative paperwork was never processed. For a long time, Stowers’ story—and the documents to prove it—were sidelined.

Following the Civil War, 25 Black soldiers were bestowed the Medal of Honor for their gallant service, but of the 119 World War I Recipients, not a single African American had earned a Medal. Certainly, there were stories of courageous service—where were they?

In 1988, the Army conducted an in-depth review to understand why Black soldiers had been overlooked during World War I. Eventually, Stowers’ record came to light. The Pentagon expedited the formal processing, and on April 24, 1991, President George H. W. Bush posthumously presented Stowers’ Medal of Honor to his sisters, Mary Bowens and Georgiana Palmer. Stowers’ heroic sacrifice forever endures through his legacy—both in name and selfless acts of integrity.

The error opened a floodgate; the Army continued to review cases of African American soldiers who were denied the Medal of Honor due to racial bias. The findings concluded that eight Black men—seven who served in World War II and one additional service member from World War I—had been overlooked. The men received the Medal posthumously in 1997 and 2015. Even today, the Army continues to review cases.